Introduction

Effective communication is the bedrock of balancing performance and perception in the private security and safety industry. It is a challenge the profession must not underestimate. Breakdowns in communication may result in loss of clients, high employee turnover, harm to life and property, and lawsuits.

Because the stakes are so high, private security and safety agencies must dedicate themselves to the development, articulation, and practice of methods that allow for on-going evaluation of client needs and service delivery. That assessment process, as illustrated in these pages, is one that shares decision-making among managers and front-line practitioners. In so doing, private security and safety businesses can provide clients with tailor-made solutions to problems in the diverse environments where they live and work.

How does performance in our arena meet the perception of clients, employees, peers, the public, and the industry as a whole? What kind of model is the best model for ensuring such excellence in leadership? In this essay, we posit that management of systems, methodology, and infrastructure involves assessing an agency’s efficiency and effectiveness through thoughtful discretionary use of procedures and control points in areas of operations, in which effectiveness takes precedent over efficiency in the overall performance model. Moreover, we maintain that high quality leadership in private security and safety harmonizes performance and perception by allowing front-line practitioners to follow the “science” of procedures while also permitting them to practice the art of adaptation in day-to-day operations. With these ideas in mind, we offer private security and safety leaders a fresh model upon which they may formulate their agencies’ strategic decisions and tactical actions.

In the pages that follow, we explore the interplay of main viewpoints that influence the outputs of this decisional model, the types of environments that influence the strategic and tactical choices embedded within those outputs, and the essential kinds of strategic analysis and tactical actions for application in those environments. Afterward, we reconsider the implications for leadership in private security and safety by challenging private security and safety leaders to resist the temptation of purist efficiency models that may prove counterproductive in the communities they are charged to protect.

End-Users, Officers, and Command Staff: An Interplay of Main Viewpoints

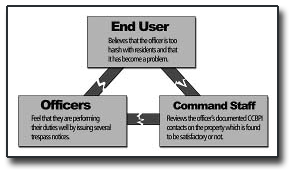

Explanation of a model for judging how well clients and private security and safety agencies perceive performance necessitates an overview of the viewpoints of the model’s primary stakeholders: end-users, officers, and command staff.

The first viewpoint is that of end-users, who have their own sets of expectations for private security and safety services. For example, if an agency were providing uniformed security services in a bank, then the bank client, bank employees, and customers would be the end-users of that agency’s services.

The expectations of end-users influence their perception of agency performance. Formation of their viewpoint hinges upon the actual service delivery by front-line practitioners. In addition, end-users base their judgment of that service delivery on the actions of officers and their interactions with them. In other words, end-users formulate judgments about quality of service on their daily relational experiences with the officers assigned to them. Having formed those judgments without prior objective knowledge about why officers act in a particular manner, they interpret the effectiveness of agency performance through a filter of subjectivity. These end-users perceive, accurately or not, agency performance.

The second viewpoint is that of officers, who are the front-line practitioners providing service delivery to agency clients. These individuals also form their own viewpoints about the performance of their duties, especially whether they meet end-user and command staff expectations.

The interpretation by officers of the services being delivered may be very different than that of end-users. For example, officers may believe that their performance is satisfactory because they know they are conducting security operations within agency protocol. End-users, however, may not hold the same view. This discrepancy could be caused by very minor things, such as the appearance of the officers, to more business-oriented issues, such as the officers not being customer-friendly toward guests of the assigned facility.

The third viewpoint is that of command staff, who are responsible for the security deployment of front-line practitioners. Moreover, command staff answer to executive staff, who themselves hold the responsibility of maintaining positive client relations. These combined senior staff may formulate a very different view than either that of end-users receiving or officers providing agency services. Managing practitioners interpret the quality of performance in the field from a different place and from a different angle. Invariably, these managing practitioners form their opinions based on limited information that surfaces to the top of the chain of command from the field and from the clients.

Unless managing practitioners are aggressive in their communicating directly with the field and its end-users, information may surface only when problems have escalated beyond the point of being managed effectively in the field. When information reflecting perceptions of unsatisfactory service becomes available to command and executive staff, it often comes as a surprise to them.

While private security and safety agencies should encourage field supervision staff to try to solve problems at their level, those same agencies should expect nonetheless that any bad news will be shared up the line of communication to senior staff. For, if not, the breach in communication may result in an error of perception: Managers will believe that performance in the field is satisfactory until the bad news surfaces. They will be that last to learn that performance does not equal perception.

Nor should absence of end-user complaints or concerns about performance equate to the automatic assumption of client satisfaction. For example, managing practitioners assigned to oversee accounts may become aware of serious operational problems that have been festering for months, yet have not received a complaint from end-users until a totality of circumstances come into sharp focus during a client meeting.

Primary Stakeholders’ Fractured Perceptions of Agency Performance

As illustrated in the diagram above, it is entirely possible that end-users, officers, and command staff may hold fractured perceptions of agency performance. In our experience and discussed in depth below, models of efficiency giving rise to measurable, procedure-driven tactics in the field contribute to the illusions these stakeholders may hold. When there are breakdowns in communication among all three groups about performance expectations, the illusions of these stakeholders shatter. In turn, this creates a very difficult environment to assess and analyze. At that point, problems can reach critical mass and that is when an agency is met with litigation and loss of reputation.

Leaders in private security and safety are responsible for protecting people who have entrusted their security and safety to those leaders. If all individuals working in the private security and safety industry act with that in mind, balancing performance and perception is achievable. Individual actions produce consequences that may cascade throughout an entire organization, for better or worse. So when command and executive staff do learn about problems in the field, their role is to assess the problem, sort out truth from fiction, and then arrive at corrective measures for correcting the dysfunction in the most expedient manner. The charge of managers is to make sure that the reality of performance is equal to the perception of what our end-users believe agency field-practitioners should be doing.

A Feedback Model for Balancing Performance and Perception

In this section, we articulate a feedback model of combined strategic and tactical decision-making to reach an agency’s desired equilibrium of performance and perception.

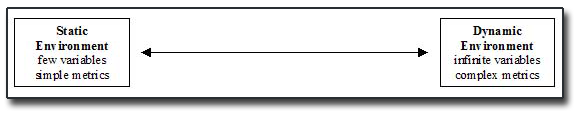

First, private security and safety leaders define the types of environments they are charged to protect. They may recognize these environments, generally, as static and dynamic.

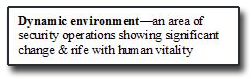

Second, in consideration of those types of environments, private security and safety leaders then ask certain questions: “To what extent do we care that we are effective?” “To what extent do we care that we are efficient?” “To what extent do we emphasize the role of control points? and “To what extent do we emphasize the role of procedures?”

Whereas the first and second questions above focus on the mindset of managing practitioners who operate an agency, the third and fourth questions focus on front-line practitioners who work in the field. Moreover, while efficiency and effectiveness underpin strategic decision-making by agency managers, procedures and control points involve tactical decision-making for front-line practitioners.

The significance of these aggregate business and operational concepts are further explored in the sub-sections that follow. For the remainder of this section, however, we offer some basic assumptions about them:

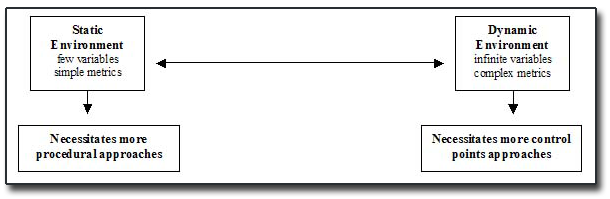

- In a purely static environment, efficiency and procedures might be an agency’s guiding principles; whereas in a purely dynamic environment, effectiveness and control points might produce the results that agency seeks.

- A comprehensive approach to addressing performance and perception dilemmas, assessment of efficiency and effectiveness further enables private security and safety leaders to define priorities within the organization and analyze conflicts among end-users, officers, and command staff.

Furthermore, how we think about and apply these concepts in different environments will determine how well our performance squares with the perceptions of our end-users, officers, and command staff.

In the static environment, say an industrial or manufacturing facility, how agencies and their end-users perceive agency performance may mean ensuring that certain gauges are read within certain parameters, certain doors are opened and closed at given times, or that this or that switch is in its correct position. As such, these mechanical things need to be checked regularly and adjusted as necessary.

At the other end of this spectrum, the dynamic environment, perhaps an apartment community in a culturally diverse and crime-ridden community, how end-users and agencies perceive performance means something poles apart from what is meant in the manufacturing plant, which is more measurable than the apartment complex.

So, on the one end private security and safety leaders have a static environment where only a few variables need monitoring, and on the other end they have a very dynamic environment where there is an infinite number of variables at play at any given time (Figure 2).

Area of Operations Spectrum

Estimation of the nature of that area of operations determines our selection of procedures and control points–those tactical possibilities to help determine how to manage and direct a chosen level of efficiency in order to achieve a desired goal of effectiveness (Figure 3).

Tactical Possibilities for Static and Dynamic Areas of Operations

The process of analysis leading to judgment about whether effectiveness or efficiency represents primary managerial concern and whether procedures or control points represents primary tactical concern is similar to that of the OODA model used by military planners in their own areas of operations. The acronym stands for “Orientation, Observation, Decision, Action.” This model is intended for upper-level managers far removed from the battlespace inasmuch as it is intended for boots on the ground. When confronted with a particular area of operations, planners and troops orient themselves to that space, observe it, decide what to do about it, and take action in it. The feedback model may be repeated as necessary, in order to make adjustments based on the needs of the moment. So in effect, the exercise of leadership is not limited to those at the highest rungs in the chain of command.

The hypothetical cases below illustrate how private security and safety agencies might make strategic decisions and take tactical actions in purely static or purely dynamic environments, based on their questions about the roles of efficiency, effectiveness, procedures, and control points in those areas of operations.

Decisional Analysis and Action for Static Environments

For purposes of illustration, a facility with highly pressurized machinery is an example of a static environment. In this environment, machines and not humans dominate the lay of the land. The private, closed, mechanical nature of this facility renders what happens inside it highly predictable. Assigned to protect such a facility, an agency would conduct an initial assessment of it by orienting itself to and observing that environment.

For managers in our industry, that geographical area of operations is unambiguous and easy to measure. Therefore, in terms of strategic assessment for meeting client security and safety needs in this scenario, those same managers invariably would apply an efficiency model for managing its resources and measuring its performance. A model of efficiency will have been sought because it is feasible in this highly static environment.

At this point in the feedback loop, agency managers will have moved from orientation and observation and into a decisional phase leading to action involving the agency’s implementation of an operational plan and deployment of resources. A “scientific” strategic and tactical plan will have been selected.

What our industry refers to as the “science” of safety holds our attention in many ways, from forensics to the employment of technology to target vulnerabilities assessments to patrol procedures. Furthermore, this “science” delivers a managerial method, systematizing policies and procedures and fostering intelligent planning and resource usage. Often, “science” equates to a default setting for operations. I maintain that this is a valid approach for static environments but–and as I will illustrate below–is invalid for dynamic ones.

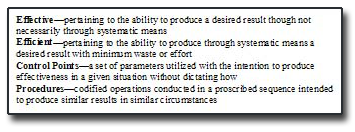

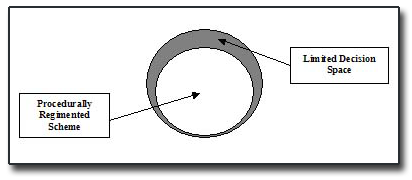

Often thought of as a set of linear exactitudes to lead front-line practitioners through specific routines, procedures offer a blueprint of efficiency for day-to-day routines. Many patrol services, for example, require their officers utilize DETEX or similar control devices commonly referred to as “guard tour systems” to ensure that front-line practitioners properly work “according to plan.” With these systems, patrol officers are given timetables to maintain (i.e., procedures), which creates a ruler to measure performance. Usually, establishing patrol routes along with time frames dictate how much time is spent at each location. This time allotment could be around 15 minutes and might involve three or four visits per night at each location.

These systems of tactical action deliver excellent performance in static environments where machinery–as opposed to humans–is the major feature of the environment. Established tour system routines allow officers to go from one critical asset to the next, repeating the safety patrol as needed. Hence, in the case of a facility requiring the protection of critical fixed assets, the tour system is an appropriate tool for achieving an agency’s performance.

In this scenario, front-line practitioners working in the facility with highly pressurized machinery are analogous to trains running on a set of tracks. Tracks restrict the movement of the train, permitting little deviation with no adverse effect on performance. The train travels at a certain speed, makes certain stops, and–barring extraordinary circumstances–arrives to its destinations on time.

Decisional Analysis and Action for Dynamic Environments

In contrast to the facility with highly pressurized machinery, an apartment complex in a high-risk community exemplifies a dynamic environment. In this environment, humans are abundant, diverse, and unpredictable. This environment is also more public and open than the facility with machines in it.

In having oriented themselves to and in having observed the high-risk apartment complex, leaders in private safety will have made strategic decisions and implemented tactical actions decidedly different than those in the scenario above.

In a dynamic environment, the “science” of the security profession still matters; however, at this end of the continuum what leaders may call the “art” of safety is essential to successful agency performance. “Art” implies creative adaptation to particular circumstances instead of adherence to fixed operational plans. “Art” also allows friendship to develop between those entrusted with providing safety and those who require the service. “Art” also involves honesty, character, and integrity in the functional aspects of that same service. Furthermore, “art” implies a meaningful understanding of the constituencies served, with the promise to listen and respond in ways that are consistent with community needs.

The artistic components of practitioners’ skill sets allow them to be effective at working through the human predicaments they encounter in the field. “Art” expressly requires that the protection firm be engaged for the long haul in the life of the community being protected. In addition, “art” allows the practitioner to consider alternatives to community problems identified that may not necessarily be real legal matters. In large part, performing the “art” of the safety profession allows the practitioner to address demanding tasks with interpersonal communication skills with sophistication and sensitivity.

Control Points and the “Art” of “Anti-Procedures”

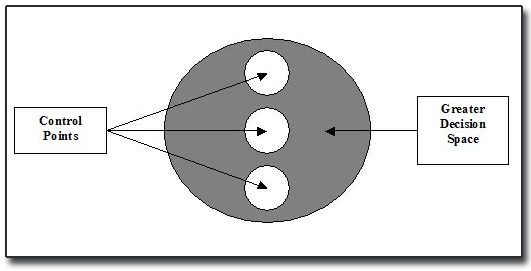

Because the procedural metrics used for static environments lose their value to managers in dynamic environments, agencies instead may use control points, which give front-line practitioners that much-needed flexibility to manage areas of operations.

Control points are sets of parameters carried out with the promise of resolving effectively any given situation without dictating how. They are loosely defined, couched in non-specific terms. Moreover, control points are behavioral guidelines for practitioners. They are painted with broad brushstrokes allowing practitioners to bring their own “art” to the canvas, instead of someone else’s paint-by-number system that diminishes imagination.

In contrast to procedures, control points are not regimented schemes of metrics and directives that are better suited for static environments. So as environments become more and more dynamic, managers can phase out procedures and bring in control points, allowing for adaptive decision-making in dynamic environments.

Whereas procedures intentionally create structure focused at providing consistency in delivery of services, control points are markers enabling front-line practitioners’ ingenuity to play as large a role as possible.

In a dynamic environment like the aforementioned apartment complex, a more efficiency-focused model never can deliver the requisite flexible platform for solving human-related problems. That is because dynamic environments resist codified routines like the “guided tour system,” which is based on the most minimum resources required.

Indeed, reliance on such “old favorites” may prove counterproductive and perhaps even illusory. Not meaningful in the dynamic landscapes our front-line practitioners are assigned, procedures can be downright dangerous, in terms of the liability, if agencies insist on using them.

Procedures and control points also differ from one another in that procedures are based on an individual’s ability to follow orders and to work within a strict regiment of behavioral patterns. Procedures tell front-line practitioners who to be, what to do, when to do it, and where to do it.

As depicted in the diagram below, procedures dominate and limit what I call the “decision space” of front-line practitioners, assuming there is any.

Encroachment of Procedures on Front-line Practitioner’s

However, control points center upon why officers do what they do or what the purpose of their function is. They compel officers to consider the underlying philosophy of their actions.

More importantly, control points promote leadership where, arguably, it is needed most, in the communities private security and safety agencies serve. As depicted in the diagram below, control points expand the decision space of front-line practitioners.

Paradoxically, and further articulated in the next sub-section below, application of anti-control points is predicated on the need in a dynamic environment to expand decision space (Figure 5).

Expansion of Front-line Practitioners’ Abilities to Make Effective Choices in Dynamic Environments

Toward Further Determination of Tactical Choices:

Control Points and Anti-Control Points

Within its feedback model, we further distinguish between control points and anti-control points that determine the decisions and actions undertaken in an area of operations. We make this distinction because even a set of parameters could become meaningless in some of the dynamic environments in which front-line practitioners operate.

With anti-control points managers purposefully do not task officers with specificity in their routes. Either they intentionally eliminate control points from the tactical schema, or they never implement them; and in so doing, or not doing, managers increase the range of decision space in their areas of operations. In turn, officers may apply their own creative powers to intelligently work in those dynamic environments.

Anti-control points pose particular implications for accountability. As managers remove control points from the dynamic environment, estimation officers’ performance shifts toward the back end of an assignment, such as when GPS tracking data are compared and contrasted with officers’ incident and time reports, and then later compared and contrasted with data gleaned from end-users. This requires more work on behalf of supervisors in that they themselves must synthesize data, formulating a holistic picture of whether performance and perception are in balance.

Finally, the nature of decision-making changes with application of anti-control points, increasing what is commonly called the “bottom-up” style. Decisions made by front-line practitioners hinge upon a strong sense of trust between command staff and officers in the field. That is because the difference between the two control points subgroups is predicated upon, one, the degree of influence exerted by command staff on practitioners in the field, and two, the level of freedom held by practitioners in the field to decide what kinds of decisions and actions they take–excepting, of course, company policies, ethics, and rule of law. As managers forfeit their direct decisional control to officers, they hand over their decisional freedom to those same officers. In the process, the concept of leadership is further infused among all rungs of the agency.

To further illustrate by example the role of anti-control points, recall first from the vehicle deployment scenario above that managers have charged officers with the responsibility to visit a given set of sites, in effect, telling them that they must do what they must at those sites in order to be effective. In that scenario, managers might have provided some directives and metrics in the form of reporting requirements or site specifics, and they might further monitor those same officers through GPS, the same reporting requirements, and client feedback. These are all control points.

But what if some of the control points were removed from front-line practitioners’ frames of reference? To invoke once again the multi-lane highway example, the concrete median (i.e., a control point) now no longer exists, offering opposing lanes of traffic more options for maneuver. Only the guardrails remain, or in the case of vehicle deployment, the area of operations itself.

Or comparatively, in the example of the apartment complex, removal of a control point would involve the absence of a mandate that officers visit certain locations within an assigned area of operations. In turn, officers may visit all locations in the area of operations, depending on the needs of the day and knowledge about the environment.

In other words, in deciding to use anti-control points to expand decision space in the field, managers say to officers, “Here is an area of operations for you to manage, you know what kinds of tools you have in your box to manage it, so we trust you to use those tools at your discretion.”

Control Points and the Character of Front-line Practitioners

In order to be effective in private security and safety, field practitioners need the flexibility of control points to think on their own when faced with human-generated conflicts. In turn, those same parameters raise the bar of standards for the types of front-line practitioners agencies hire: officers must possess excellent critical thinking ability, communication skills, personal demeanor, self-possession, empathy, sensitivity, focus, total commitment, and a host of other attributes that form the foundation for practitioners to be effective within the security environment.

Control points also rely on the honor, integrity, intelligence, and free will of practitioners, while procedures reinforce traits of consistency that would otherwise cause every employee act the same way in every situation–or, worse yet, not at all. Uniformity is very efficient; however, in the amorphous environments where private safety agencies operate, it isn’t necessarily effective. Private security and safety agencies must seek artistic practitioners who take the tools they have and work within a control point environment while staying within the spirit of the policy guidelines. Artistic practitioners are people who effectively utilize such latitude with responsible, sober conduct.

If agencies were confronted with purely static areas in which managers might select only procedures as the appropriate means for producing good results in area of operations, front-line practitioners need not possess such character. Agencies could lower standards by hiring people who are merely good at following linear orders, who can count, and who can fill out a simple form. The reality is, however, that most areas of operations are a mixed environment combined with mechanical things or buildings requiring periodic safety and security checks and people requiring an understanding that transcends tight procedural controls. In that mixed environment, managers and practitioners can employ both procedures and control points, recognizing that the more dynamic the decision space is, the more significant control points and anti-control points become in the operational schema. Minimum resources coupled with routines premised on minimum effort become therefore a secondary support mechanism–a “bolt-on” strategy that is usually in the form of a procedure to make a function operate more smoothly in a mixed environment.

So effectiveness supersedes efficiency in this feedback model for determining performance. A focus on efficiency and its tempting reliance on procedures never can deliver the requisite flexible platform for solving human-related issues. Efficiency models should not undermine performance. To the contrary, they should enhance it. When human lives are at risk, effectiveness must be the measuring stick of success. This is especially true in operating private security and safety agencies. Effectiveness should be the end result leaders in private security and safety look for in order for their agencies to grow responsibly while maintaining their reputations for excellence.

Implications for Leadership: Avoiding “Efficiency Creep”

How can we call ourselves “leaders” if efficiency is all that we are and procedures are all that we do? How can we call ourselves “leaders” if only the managers in our agencies think of themselves as “leaders’?

Leaders in the private security and safety industry are responsible for “getting the job done” and in taking corrective action when that job is not “getting done.” In that respect, efficiency and effectiveness organizational assessment models remain a constant source of concern. We maintain, therefore, that inflexible procedures and efficiency-based models of strategy and tactics are counterproductive illusions in the dynamic environments we are charged to protect.

Experience suggests that our primary stakeholders become disillusioned when we have let the linear mindset of efficiency seep in because efficiency-driven decisions undermine our mission to protect life and property. One example to which most can relate involves our nation’s efforts to reduce school crime. Here, we have seen the proliferation of zero-tolerance policies in K-12 education. Zero-tolerance allows no leeway in decision-making, stifling the art of practicing public safety. Most readers have heard of zero-tolerance cases in which policy is interpreted so uncompromisingly that schools have expelled students in good standing and no history of criminal behavior. A young woman with a bottle of Midol given to her by her mother should not be characterized as if she were in possession of illicit drugs. A student who inadvertently leaves a kitchen knife in her car after a family picnic should not be treated as a criminal in possession of a lethal weapon. Similarly, the latitude we give our officers is essential for turning crime-ridden, moribund environments into enclaves of peace and vitality. On a case-by-case basis, officers need room to draw distinctions.

Where managers think and worry about efficiency, strategic minds think and worry about effectiveness. The great leader merges the two. He sets the stage for expectations of effectiveness and how that can be gauged. He also creates metrics that allow performance to be monitored so managers can ensure it is line with, or working toward the ultimate goal of effectiveness. More importantly, however, the great leader infuses the concept of leadership throughout the entire organization by implementing performance models that encourage front-line practitioners to fully realize their creative faculties.

Even outside the private security and safety arena, efficiency is the standard for measuring how well a business performs. Efficiency is the desired focus, and rightly so, because efficiency under the right conditions does achieve great performance. McDonalds is a good general example of efficiency leading and affecting good performance. Fast food establishments are so efficient that they can deliver a hamburger meal, made to order, within a few minutes of ordering. For McDonalds to be efficient makes them effective at delivering fast food because this is the service they provide.

Private security and safety, however, does not and cannot have that same luxury. Indeed, lowering quality is anathema to the security and safety imperatives of services private security and safety leaders provide. Emphasizing efficiency models as primary means to deliver services and to determine performance is irresponsible in those dynamic areas of operations where resources are deployed. For example, emphasizing efficiency to deliver services that revolve around human conflict hinders front-line practitioners’ ability to perform, dampening the impact a practitioner may bear on a given situation. Ultimately, efficiency models create an environment where poor perception of services becomes the end result of efforts.

In addition to fast food restaurants, other businesses rely upon efficiency models because the nature of those businesses demands an efficiency standard. Overnight package delivery services like FedEx or UPS rely on efficiency as a primary strategy to accomplish their business model in order to accomplish effectiveness. For example, if FedEx delivers a package in good condition by 10am the next morning, it was efficient in its systems, which enabled them to be effective in delivering that package by a deadline and ultimately in performing the services FEDEX sells. In turn, FEDEX entertains high customer satisfaction. This represents a good example of perception equaling performance through a proper balance of efficiency and effectiveness.

Despite the potential risks (e.g., death or personal injury, loss of assets, loss of credibility, lawsuits), private security and safety businesses typically favor efficiency for assessing how well they operate and serve their clients. They focus on efficiency in large part because application of instruments, means, and actions is easier to manage and measure. The larger the agency, the truer this is. Efficiency is unambiguous, whereas effectiveness is not.

Given that the private security and safety industry differs from fast delivery services such as FEDEX or UPS, the goal of private security and safety is not driven by expediency. In addition, we also should agree that the McDonalds approach of fast and cheap for lower quality food is not a responsible model for implementing protective services. So the question then becomes, “How do we ensure that the perception of our services equals our performance and that efficiency does not hinder effectiveness?”

This question is as important to answer on a day-to-day operational level as it is at the agency level. Indeed, attention to that question is vital for the growth of any private agency. In performing services involving client and end-user problems, it stands to reason private security and safety leaders want to be effective at it and not just efficient, for effectiveness signifies the ultimate standard of operational success, client retention, and client acquisition. Therefore, our managing practitioners bear responsibility for creating an environment that allows our front-line practitioners to perform the art of their profession without being constrained by stringent standards and procedures. In so doing, they allow the proverbial “boots on the ground” to be leaders, too.

Performing this art of managing situations, interacting with people, and trouble-shooting the dynamics constantly at play in the environments the private security and safety arena protects necessitates as much flexibility as can be leveraged in any given situation. For that reason, the feedback model proposed in this essay prefers effectiveness and control points for strategic decision-making and tactical applications in the field. This model is the most sensible, realistic one to apply. While the model involves strategies and tactics that are difficult to measure, achieving equilibrium between performance and perception requires that private security and safety businesses manage the process by not reducing their decisions to one-size-fits-all approaches. They do this by resisting exclusive reliance on dehumanizing, mechanized systems. By not following the proverbial “plan,” they achieve success–although they might not be able to measure it.