Mass Homicide in Schools: The Risk in Perspective

When teaching security planning workshops for school leaders, I find it valuable to begin the presentation with a brief discussion to put the risk of mass homicide in perspective. I realize in most audiences there will be a few administrators who believe such an event could never happen in their school. Conversely, I also know there may be others present holding an exaggerated fear of the threat fueled by what they have seen in headlines over the past several years.

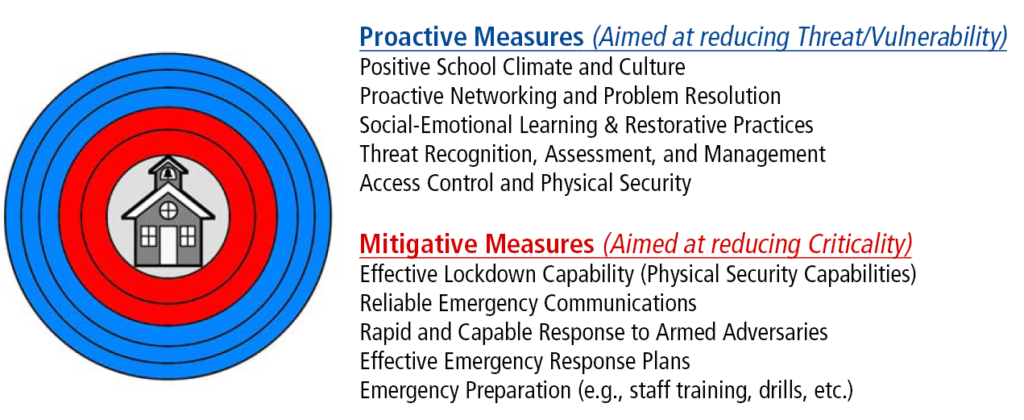

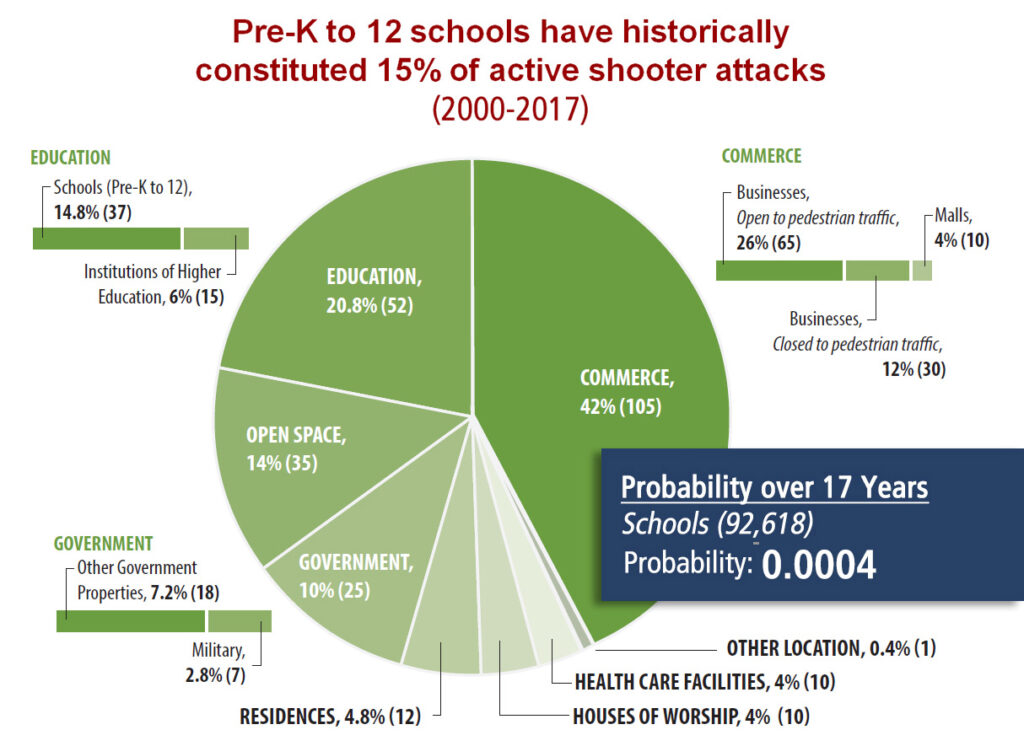

There are two factors that contribute to risk: Probability (the likelihood of occurrence of a risk event) and Criticality (the impact/severity of the risk event). Statistically, acts of mass homicide in schools are very low in frequency and rarely does probability as a sole factor justify risk reduction. For instance, the FBI documented 52 active shooter attacks in the United States between 2000 and 2017 involving educational institutions.[1] [2] [3] Considering the presence of over 92,618 K-12 schools in the US, the estimated probability of an individual school experiencing an active shooter attack over the seventeen year reporting period is 0.0004.[4]

However, the low statistical probability of active shooter risk rarely matches with public perspective. For instance, in a 2018 survey by Center for the Study of Local Issues at Anne Arundel Community College, 61% of county residents polled expressed fear of a mass shooting in local schools.[5] According to the 2018 PDK Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward Public Schools, 34% of parents reported fear for their child’s safety at school.[6] In a 2018 survey of Whatcom County public school parents, school security tied with topics of student support services and access to career and technical education opportunities as number one priorities.[7] For independent schools, security is rapidly eclipsing traditional priorities of parents (such as scholastic excellence) and perception of safety has even become an issue of business competition.

Psychologists attribute the public’s tendency to overestimate the probability of tragic events to a heuristic called availability bias.[8] This phenomenon most commonly occurs as an inaccurate deviation in judgement in response to memorable and emotionally-impactful events.[9] In today’s society, this situation is often compounded by the extended duration and dramatic presentation of news media reporting in the aftermath of tragic school shootings.

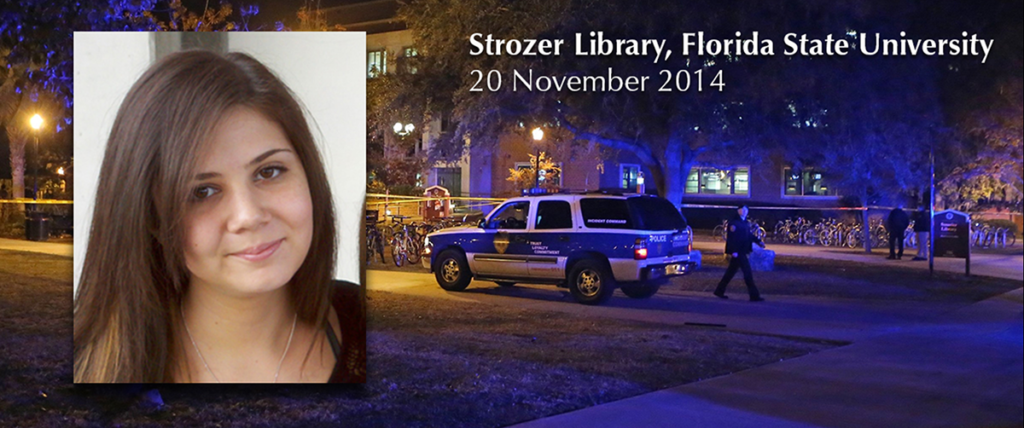

Although the probability of mass homicide is indeed very low, the threat is real nonetheless. To punctuate this point during seminars, I end discussion about risk probability with a slide displaying Florida State University’s Strozer Library and a short description of the shooting on 20 November 2014. I use that specific event as a sober example of the reality of active shooter violence because my second oldest daughter had just departed the library twenty minutes before gunman Myron May arrived and commenced fire.

Mass Homicide in Schools: Consequence as the deciding risk factor

For most schools, the probability of attack as a sole factor rarely justifies serious risk reduction. In most cases, it’s the potentially devastating consequences of an attack that warrant concern. Aside from the obvious and horrific impact of loss of life, active shooter attacks universally result in extended disruption of school operations, loss of student enrollments, and diversion of leadership attention to crisis management activities. The duration of disruption can extend months before police have released the school as a crime scene, cleanup and restoration is completed, and post-incident recovery activities have concluded.

An act of mass homicide can literally close the doors on a school forever. In cases where the horror of the event is deeply imprinted into the psyche of the public, the school may be deemed permanently inhabitable due to its presence as a reminder of the tragedy. Rather than repair and restore Sandy Hook Elementary School, Newtown Public Schools opted to demolish the building and build a new replacement school at an estimated cost of $50M.[10] Similarly, Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Act authorized $25 million to replace building 12 in Parkland, Florida.

Depending the school’s responsiveness in managing the post-incident psychological consequences, the effects of an attack can easily result in exodus of students and school employees and long-term negative impact on climate and culture. In addition to psychological wounds suffered by the school population, the trauma of mass homicide can extend far beyond the local community with measurable effects of sadness and anxiety experienced vicariously by people nationwide.[11]

When these issues are rationally and objectively viewed from the perspective of risk, it is usually the combined results of duty of care obligation (legal and moral responsibility for student safety), parental perceptions and expectations, and the potentially catastrophic consequences of an attack that warrant a balanced and diligent approach to risk control in schools.

[1] UFC 4-023-07, Design To Resist Direct Fire Weapons Effects. US Department of Defense, N.p.: 2008.

[2] Ibid. pp. 2-1

[3] UL 752, Standard for Bullet-Resisting Equipment. UL, N.p.: 2005.

[4] ASTM F3038-14, Standard Test Method for Timed Evaluation of Forced-Entry-Resistant Systems, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2014

[5] NIJ Standard-0101.06, Ballistic Resistance of Body Armor. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC, 2008.

[6] SD-STD-01.01, Revision G. Certification Standard. Forced Entry and Ballistic Resistance of Structural Systems. U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Diplomatic Security, Washington, DC, 1993.

[7] EN 1063:2000, Glass in building – Security glazing – Testing and classification of resistance against bullet attack. European Committee for Standardization, Brussels, 2000.

[8] EN 1522:1999, Windows, doors, shutters and blinds. Bullet resistance. Requirements and classification. European Committee for Standardization, Brussels, 1999.

[9] “5.56×45 versus 7.62×39 – Cartridge Comparison.” SWGGUN. SWGGUN, N.p. https://www.swggun.org/5-56-vs-7-62/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2017.

Craig Gundry

Copyright © 2019 by Craig S. Gundry, PSP, cATO, CHS-III

CIS consultants offer a range of services to assist schools in managing risks of active shooter violence. Contact us for more information.

References

[1] Blair, J. Pete, and Schweit, Katherine W. (2014). A Study of Active Shooter Incidents 2000-2013. Texas State University and Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, D.C. 2014.

[2] Active Shooter Incidents in the United States in 2014 and 2015, Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, D.C. 2016.

[3] Active Shooter Incidents in the United States in 2016 and 2017, Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, D.C. 2018.

[4] U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2018). Digest of Education Statistics, 2016 (NCES 2017-094), Chapter 2.

[5] County Survey Finds Support for Gun Control, Concerns About Mass Shooting at Schools. Press Release: April 5, 2018. Center for the Study of Local Issues, Anne Arundel Community College.

[6] School security: Is your child safe at school? – PDK Poll 2018. http://pdkpoll.org/results/school-security-is-your-child-safe-at-school

[7] OSPI NEWS RELEASE: Counseling, Mental Health Top Priority, Public Says. Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. August 28, 2018.

[8] Tversky, Amos; Kahneman, Daniel (1973). “Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability”. Cognitive Psychology. 5 (2): 207–232.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Delgadillo, Natalie. With Shootings on the Rise, Schools Turn to ‘Active Shooter’ Insurance. http://www.governing.com/topics/education/gov-cost-of-active-shooters-insurance.html. June 2018.

[11] Dore, B., Ort, L., Braverman, O., & Ochsner, K. N. (2015). Sadness shifts to anxiety over time and distance from the national tragedy in Newtown, Connecticut. Psychological Science, 26(4), 363–373.