Considerations for Designing Active Shooter Protection Measures (Pt. 4)

Parts 1 and 3 of this series surveyed important principles of physical security and facility preparation for mitigating the consequences of active shooter attacks. Although the concepts described in the preceding articles are universal, there are often unique circumstances that influence how these principles are best applied in different situations.

The following are some preliminary questions to consider with bearing on the practicality and prioritization of security measures.

Is it feasible to employ restrictive entry control and screening measures?

In an ideal situation, entrance into the facility is channeled to a limited number of secured entry points and all entrants are subject to verification and weapons screening before admittance. However, there are many situations where restrictive entry controls are impractical (or impossible) due to reasons of high volume of public traffic, cultural expectations, budget, or low-risk justification. Common examples of this situation include malls, hotels, train stations, entertainment districts, houses of worship, hospitals, multi-tenant office buildings, and similar facilities. This is also a common situation in schools and universities with complex campuses, or where concerns about negative impact on school climate, cost, and operational burden outweigh the risk.

In these situations, an adversary could access populated areas of the facility undetected before commencing an attack. To compensate for this, high priority should be given to measures that simplify rapid escape from public areas and expedite the actions of armed responders. In large buildings (such as multi-level office buildings, schools, hospitals, and hotels), alert communication is critical and safe refuge options should be abundantly available for people unable to escape or who are unaware of the threat’s location.

Although restrictive entry control may not be practical in these cases, it may be worth configuring an access control macro to facilitate the rapid lockdown of exterior doors and high-risk indoor locations if an attack is detected outdoors.

Are there groups of occupants present whose capability to respond is likely impaired or who are unable to easily evacuate during an attack?

This is generally the case in schools, daycare facilities, nursing homes, and hospitals. In these situations, alert communications and ensuring the availability of safe refuge areas are top priorities. In schools and daycare centers, all classrooms should meet criteria as basic-level safe rooms. In hospitals and nursing facilities where it is not feasible to secure patient rooms, measures should be implemented to rapidly secure wards and hallways wings occupied by vulnerable groups. Additionally, all employees caring for vulnerable populations should be trained in lockdown procedures and drill regularly to ensure reliable performance under stress.

In nightclubs and entertainment venues, we often have a different type of concern—alcohol. When considering other conditions typical in nightclubs and party venues (e.g., dense crowds, low lighting, loud music, light shows, etc.), alcohol is the final ingredient in a recipe for disaster. In previous nightclub attacks (e.g., Pulse, Reina, Bataclan Theater, etc.), the reaction of patrons was initially delayed by confusion and followed immediately by panic as occupants fled the direction of danger. To address this concern, priority should be given to designing intuitive and high capacity egress routes in directions away from the main entrance. Ideal preparation also includes options for direct escape from all locations inside the building (incl. restrooms, service hallways, etc.). To further address the problem of confusion, measures should be explored for quickly shutting off the A/V system and illuminating exit doors.

Are there large numbers of people present who are expectedly unfamiliar with the facility?

If yes, careful consideration should be given in the design and marking of egress routes, public notification systems, and training employees in procedures for directing guests’ response.

Does the interior layout of existing buildings provide ample options for occupants to take safe refuge?

In schools, hotels, and many office buildings, the existing indoor layout usually provides adequate options for designating rooms which can be easily upgraded to meet basic requirements as safe rooms. Where I often encounter problems with this matter are industrial facilities, telephone call centers, and office buildings with extensive use of indoor glass walls.

If budget permits, the preferred remedy is to construct (or upgrade) several intrusion-resistant rooms throughout the facility to provide accessible refuge options for employees regardless of location. As a minimum, we recommend at least one safe room per floor wing with adequate capacity for all employees in proximity. In call centers and office buildings with open floor plans, the newly constructed safe rooms can often serve a practical role as conference rooms during day-to-day activities.

If constructing safe rooms where needed is not possible, egress routes should be easily accessible and discharge directly outdoors. Additionally, employees should be trained to know that hiding in an unsecured work area is unsafe and escape is the preferred response when possible. Training should also include a discussion about optional egress paths (e.g., alternative exits, roof access, etc.) and high-risk areas to avoid during evacuation (such as first floor lobbies and central hallways).

If circumstances dictate that escape is the preferred response, situational awareness is critical and measures should be explored for monitoring the movement of attackers by CCTV and relaying real-time updates to employees.

Do cultural expectations or public image concerns restrict the employment of high profile security measures?

This issue frequently arises in corporate and hospitality facilities conscientious about branding. Many schools are also sensitive to this matter considering research by psychologists warning of the potential for negative impact on school climate. In many cases, this concern can be easily addressed by employing locks, barriers, and other hardware with a low profile appearance. Egress design, communications systems, and other infrastructure preparations are generally unnoticed by employees and the public.

Where concerns about high profile measures most often influence protective strategy are decisions about posting armed officers inside the facility and implementing entry screening measures (as described earlier in this article).

As discussed throughout this series, few measures offer as much benefit during an attack as having an on-site armed response force. If an organization is attracted to the idea of armed protection, but hesitant due to public image concerns, some measures can be employed to address this situation.

One option is to stage armed response officers in a location out of public view. Several years ago we aided an organization in evaluating potential security strategies for a parliament building. At the time, the facility was protected by several police officers armed with handguns posted outdoors. Considering the facility’s risk profile and Design Basis Threat (terrorists armed with assault rifles), we strongly recommended they augment their current security force with an on-site tactical response team equipped with military small arms. This proposal was initially rejected due to public image concerns. Our recommendation, in turn, was to stage the team inside a room hidden from public view and within 120 seconds travel time to all critical locations inside the facility. This same approach can be adopted in office buildings, hotels, schools, and any other location where public image is a concern.

Other methods for addressing this concern include substituting plainclothes officers for uniformed personnel and carefully selecting officers for their unique combination of tactical capabilities and interpersonal relations skills.

Is it expectedly safe for people to evacuate the facility during an attack, or is the facility located in a geographic area where escape outdoors is impractical or possibly dangerous?

This is not generally a concern for most facilities. Where this issue most often arises is when a facility is remotely located away from civilization or in hostile threat environments. An example of the first situation would be the Tigantourine gas facility in Algeria targeted by Al-Mourabitoun in 2013. An example of the second situation might be a compound located in a war zone where friendly authorities have little control and hostile actors abound (e.g., 2012 Benghazi attacks).

In these situations, on-site armed response capability is paramount. Additionally, perimeter defensive measures should be designed to provide the armed response force with a tactical advantage and create time for occupants to seek refuge. Additionally, safe havens should be provided capable of advanced delay times and sustained life support under attack by fire, smoke, and other methods of asphyxiation.

Is it feasible to have an on-site armed response capability?

As detailed in Part 1 of this series, barriers need to be designed to delay an adversary’s ingress into populated areas with sufficient time for a response force to intervene. If it is not possible to have an on-site armed response capability, the emphasis often needs to be placed on measures that facilitate delay (e.g., barrier construction, egress design, etc.) and expedite the response of local police.

Are we located in a region where previous incidents often result in a siege or delayed intervention by security forces?

If yes, there may be justification for upgrading safe rooms to an intermediate or high level of protection. As discussed in Part 2 of this series, most previous attacks where adversaries committed time and effort to forcibly enter rooms were in situations where authorities delayed entry. As an added measure, safe rooms in these cases should be equipped with supplies to sustain occupants for the duration of a siege.

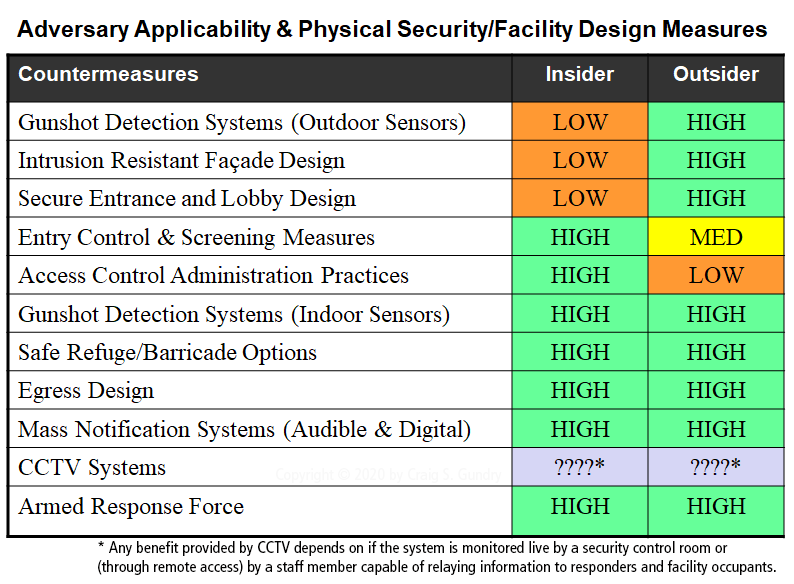

Is our Design Basis Threat adversary an insider, outsider, or both?

As explored in Part 2 of this series, the relevancy of many protective measures is directly related to the attacker’s expected access to the facility. The following table is provided as a general guide to the applicability of physical security and facility design measures to different categories of adversary.

These are some of the many questions to consider as part of the physical security and facility design process. In upcoming articles, we’ll explore these issues in greater depth and present examples of how custom protection strategies can be designed for different types of facilities.

The Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS), Situational Awareness, and Active Shooter Attacks

Another important issue to consider in active shooter planning is the potential effects of the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) and lack of situational awareness on employee response.

During life-threatening emergencies, the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) is often activated. The SNS governs human flight-or-fight response to imminent threat situations. Although the SNS served an important survival function in human evolution, its effects can impair response actions by building occupants during high-stress events. When the SNS awakens, a person’s heart rate may exceed 200 bpm resulting in cognitive impairment, loss of fine motor skills, irrational behavior, or freezing.[1]

In addition to the SNS, rarely during armed attacks do employees have real-time situational awareness of the attacker’s location and activity. The combined effects of the SNS and lack of situational awareness may result in dangerous and sometimes irrational behavior. For example, employees may be hesitant to abandon a presently unsecured location and relocate to a nearby safe room if getting there requires moving through space they cannot see (e.g., around a corner and into another hallway). If a door is equipped with a single-cylinder lock and no thumbturn, employees may be hesitant to open the door to lock it if they fear the gunman may enter the hallway.

Effective active shooter planning should anticipate the effects of the SNS and lack of situational awareness. Every effort should be made to compensate for these challenges by simplifying the expected actions of employees. Some practical examples include establishing emergency phone numbers that are easy to remember and dial under stress, ensuring that mechanical locks on doors feature a thumbturn and do not require a key for locking, providing abundant availability of safe rooms, and ensuring that escape routes do not require complex navigation to access discharge doors.

As an additional point, employees and on-site responders are not the only ones affected during high stress events. Security control room personnel suddenly launched into action with life-and-death consequences (even when remotely located) may experience some of the same impairing effects as people in the ‘hot zone.’ For this reason, critical communications systems should be designed for simplicity and control room personnel should drill regularly to minimize delays or omission of key tasks.

As we continue in upcoming articles, specific recommendations will be offered in hope of avoiding some of the many problems witnessed in previous attacks resulting from SNS impairment and lack of situational awareness .

Craig Gundry

Copyright © 2020 by Craig S. Gundry, PSP, cATO

CIS consultants offer a range of services to assist organizations in managing risks of active shooter violence.

Contact us for more information.

One Reply to “Considerations for Designing Active Shooter Protection Measures (Pt. 4)”

Hello Mr. Gundy,

I am really enjoying reading these articles. I am unable to find parts 5 through 9. Are they available?

Regards,

David W. Giese

Sempra Energy

Corporate Security