By Craig S. Gundry, PSP, cATO, CHS-III

On 02 January 2019, the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School (MSDHS) Public Safety Commission released its initial report detailing the February 2018 tragedy at MSD High School and system failures contributing to the event. Appendix B. of the report (“Target Hardening,” pages 345-350) describes proposed measures for improved security and emergency readiness in Florida schools.

The Commission’s new report follows a previous briefing released in November 2018 where target hardening measures under consideration were first presented to the public. In December, CIS submitted a critique to the Commission regarding proposed measures under consideration with the intention of correcting a number of inaccurate statements, important omissions, and a few dangerous recommendations. To the credit of the MSDHS Public Safety Commission, several of the problems described in our previous submission to the Commission have been remedied in the new report.

Nevertheless, a number of our original concerns remain unaddressed. Although Critical Intervention Services applauds the State’s commitment to improved school security and the great effort of the MSDHS Public Safety Commission, it is our hope that spotlighting these outstanding issues will better aid Florida schools in adopting the Commission’s recommendations while avoiding potential problems resulting from the Commission’s oversight.

Concerns Regarding MSDHS ‘Hardening’ Recommendations

Following is a summary of outstanding concerns regarding physical security measures recommended in the MSDHS Public Safety Commission report.

As a Level I measure, page 345 states: “Campuses should have single ingress and egress points to the extent that is consistent with this level’s criteria of minimal cost.” As a Level II measure, page 347 states: “Fenced campuses with single ingress and egress points (could be a level III based on campus size and complexity).”

Although CIS recommends channeling access into secured campuses through a limited number of monitored entry points, the MSDHS Public Safety Commission report provides very concerning advice by recommending there be only a single egress point.

In this situation, students located outdoors during an attack are trapped unless they climb a fence to escape or encircle a campus perimeter to access a single egress point. By contrast, students located outdoors during an attack should have easy access to egress gates located abundantly around the campus perimeter. This is a very common oversight we encounter in our work as consultants with schools that have implemented fenced perimeters.

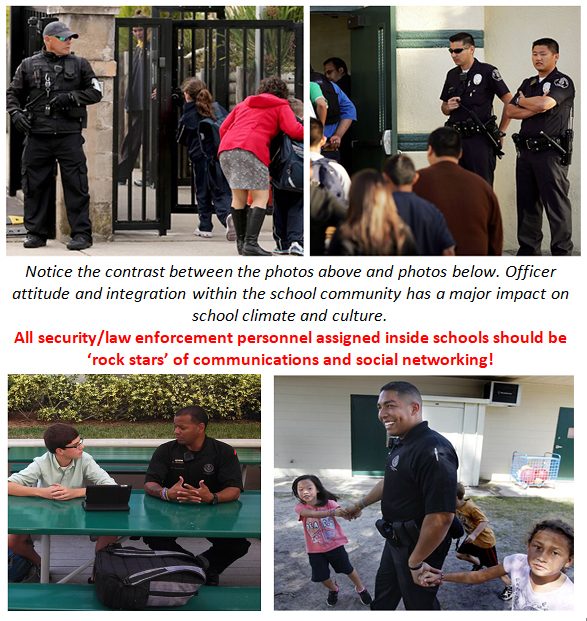

To address concerns about the exploitation of outdoor egress gates as points of entry, outdoor gates should feature mechanical exit bars and anti-manipulation features (e.g, screen mesh, acrylic panel, etc.). Exit bars featuring audible alarms can also be used to discourage exit during non-emergency situations and alert nearby staff if a student departs the campus. See the photo right as an example.

Page 347 states: “All common use closed areas in a school must have electronically controlled doors that can be locked remotely or locally with appropriate hardware on single and double doors to resist forced entry.”

Although CIS strongly endorses the use of electronic access control systems in schools, caution should be used in the selection of hardware and system configuration to avoid creating new vulnerabilities and operational problems. Regretfully, the MSDHS Public Safety Commission report does not provide guidance about access-controlled hardware selection and system configuration.

As one example of this concern, schools should strictly avoid the use of electromagnetic locks on egress doors. Building and life safety codes universally require that egress doors equipped with electromagnetic locks ‘fail safe’ (unlocked) during fire alarms.[1] In this situation, all fire alarm pull stations inside the school are ‘virtual master keys’ and would compromise most doors if someone activated a pull handle. In a number of previous attacks, fire alarms were manually activated by building occupants to alert others (e.g., 2013 Washington Navy Yard), activated by smoke or dust (e.g., 2018 Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, 2008 Taj Majal Hotel Mumbai, etc.), or used by adversaries to deceptively herd victims outdoors for ambush (e.g., 1998 Westside Middle School, 2013 UCF, 2015 Corinthia Hotel Tripoli, etc.). Conversely, when an alarm is not activated, electromagnetic locks require a push-to-exit switch or sensor to unlock egress doors when approached. In tests conducted by CIS, both methods of unlocking are often unreliable when people attempt egress under high stress conditions.

CIS strongly recommends that the MSDHS Public Safety Commission provide more detailed guidance for schools to aid with proper selection of access-controlled hardware and system configuration. (NOTE: We will be posting a new article soon to address this matter comprehensively.)

As an additional recommendation about access control, report page 349 states as a Level III measure: “RFID and Near field communications (NFC) card readers should replace all door locks on campus.”

Although RFID and NFC access control systems offer great versatility and can be very useful for controlling access into school buildings, CIS strongly discourages the use of card readers and electrified locks on classrooms which may be used as safe rooms during attacks. If the access control system in the school employs card readers and an assailant recovers an access badge from a fallen staff member, all doors with programmed access will be compromised. The report’s recommendation, as written, also contradicts other statements in Appendix B. advising that door locks be installed on all classrooms that can be locked from the inside.

CIS advises that Florida schools restrict use of access-controlled locks to exterior doors, reception lobbies, and hallway doors separating interior classroom wings.

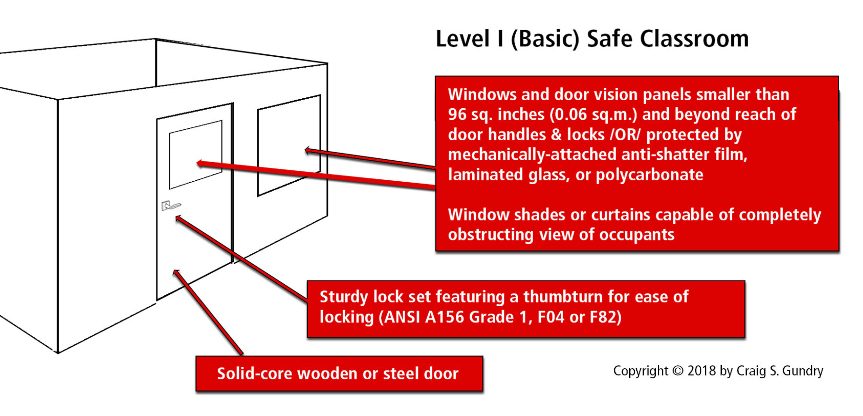

Regarding classroom doors, page 346 states: “All classroom doors should be able to be locked from inside or there must be an enforced policy that all doors remain locked at all times without exception.” Regarding events at MSDHS High School, page 45 the report states: “Individual classroom door locks could only be locked from outside the door. The teacher would have to exit their classroom and use a key to lock the door. There was no way to lock the door from within the classroom.” The related findings on page 47 state: “All of the classroom doors in Building 12 could only be locked from the exterior. Teachers inconsistently locked classroom doors and some doors were unlocked the day of the shooting. Teachers were reluctant to enter the halls to lock the doors.”

Although CIS is encouraged to see the Commission addressing concerns about standard ANSI “classroom-function” door locks, the report only addresses the matter of locking the door from the hallway-side and does not advise against locks which require a key for locking. As witnessed in a number of shooting events, doors equipped with classroom-function locks often remain unlocked due to difficulty locating or manipulating keys under stress. Some examples of incidents where this situation clearly contributed to unnecessary casualties include the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary shooting and 2007 Virginia Tech attack. In those two events alone, 26 students and faculty were killed and 24 wounded specifically because their doors could not be secured once the attack was in progress. [ii] [iii] Another recent example of an unlocked classroom due to a missing key occurred during the December 2017 shooting at Aztec High School.[iv]

The limited recommendations provided in the Commission’s report would make “classroom security function” locks (ANSI mortise F09/bored F88) permissible in Florida schools. Classroom security function locks can be locked from inside the classroom, but still require a key for locking.

CIS strongly advises against the use of all locks classified by ANSI as “classroom function.” CIS Guardian SafeSchool Program® standards recommend ANSI/BHMA A156 Grade 1 locks with an ANSI lock code of F04 or F82 (office function).[v] Mechanical locks rated ANSI/BHMA Grade 1 have been successfully evaluated under a variety of static force and torque tests. Locks coded as F04 and F82 feature buttons or thumbturns to facilitate ease of locking under stress.

As a Level I measure, page 346 states: “Classroom doors should either have no windows or every door should be equipped with a device that can readily block line of sight through the window, but does not indicate occupancy…First floor outside windows should be able to be blocked from line of sight.” As a Level III measure, page 348 states: “Install ballistic resistant glass covering on classroom interior door windows… Install classroom door windows that are small enough to restrict access and located a sufficient distance from the door handle to prevent a person from reaching through to unlock the door from the interior.”

Although these measures are sound in principle, there are several concerns with the Commission’s recommendations as presented in the report. First, the MSDHS Public Safety Commission report only recommends ballistic resistant glass on door “windows” and makes little mention about the intrusion-resistance of door vision panels, classroom hallway windows, and first floor glazing. Although it would be ideal if door vision panels were protected by ballistic-resistant glazing, such recommendations are impractical in installation and very difficult to justify from a cost-benefit perspective. A more practical and critical objective (which often can be addressed without significant expense) is delaying and deterring adversaries from breaching windows to enter occupied spaces.

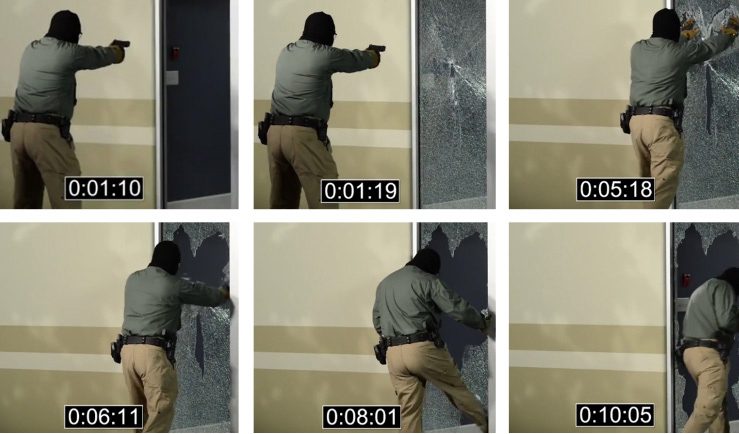

According to testing documented by Sandia National Laboratories, 0.25 inch tempered glass provides 3-9 seconds of delay against an intruder using a fire axe and the mean delay time for penetrating 1/8″ tempered glass with a hammer is 0.5 minutes.[vi] However, impact testing documented by Sandia did not account for the fragility of a tempered glass specimen after first being penetrated by firearm projectile. In penetration tests Critical Intervention Services conducted of 1/4-inch tempered glass windows using several shots from a 9mm handgun to penetrate glazing prior to impact by hand, delay time was only 10 seconds.[vii] This vulnerability was exploited by Adam Lanza during his entry into Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012.[viii]

Some practical options for upgrading existing window glazing include laminated glass, polycarbonate (for door vision panel replacement), and reinforcing existing windows with properly attached anti-shatter film. All the aforementioned options can increase the delay time performance of windows by 90 seconds or more against firearm-aided forced entry.

We strongly advise Florida schools to adopt the Guardian SafeSchool Program® standards regarding glazing and prioritize upgrade of any vulnerable tempered glass vision panels, classroom hallway windows, and first floor exterior classroom glazing prior to the Commission’s recommendations of ballistic resistant door windows.

The following is a summary of essential protective measures for classrooms suitable for refuge during imminent threat situations.

As a Level II measure, page 347 recommends: “Use protective bollards at campus entrances.”

Although anti-vehicle barriers are an effective measure to reduce the risk of vehicle ramming as a means of attack or entry, vehicle ramming has been historically rare inside the United States by comparison to other forced entry and attack techniques. This fact is also pointed out in the Commission’s report on page 14: “Vehicles have been used as weapons in terror attacks including one attack against students at a university in the US. No vehicles were used in any of the K-12 school attacks.” When approached from a cost-benefit perspective, funds allocated to installing bollards would often be better applied in addressing more critical vulnerabilities (e.g., glazing, locks, etc.).

As another matter, the effectiveness of bollards largely depends on their kinetic energy tolerance in relation to the energy generated upon vehicle impact (determined by vehicle mass and approach velocity).[ix] This issue should be carefully assessed in any situation where bollards are installed to ensure performance as expected.

If the objective of bollards is to prevent forced entry into a protected campus, requirements for utility vehicle access will also require schools to install crash-rated active barricades at vehicle gates to ensure complete protection. Specification standards relevant to active anti-vehicle barricades include ASTM F-2656-07 and/or IWA 14-1.[x] However, the price of crash-rated anti-vehicle barricades is likely far beyond the budget of most schools.

CIS recommends that Florida schools downgrade the priority of installing bollards until all other critical security improvements are completed. The unique exception to this general advice would be the protection of playgrounds located near roads and parking lots.

Craig Gundry

Copyright © 2019 by Craig S. Gundry, PSP, cATO, CHS-III

CIS Guardian SafeSchool Program® consultants offer a range of services to assist schools in managing risks of active shooter violence. Contact us for more information.

References

[1] International Code Council. International Building Code, 2012. Country Club Hills, IL: International Code Council, 2011.

[ii] Sedensky, Stephen J. Report of the State’s Attorney for the Judicial District of Danbury on the shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School and 36 Yogananda Street, Newtown, Connecticut on December 14, 2012. Danbury, Ct.: Office of the State’s Attorney. Judicial District of Danbury, 2013. Print.

[iii] Mass Shootings at Virginia Tech. April 16, 2007. Report of the Review Panel. Virginia Tech Review Panel. August 2007. pp.13.

[iv] Matthews, Justin. “Substitute unable to lock doors during shooting.” KOAT Action News. 9 December 2017. http://www.koat.com/article/substitute-unable-to-lock-doors-during-shooting/14399571. Accessed 17 December 2017.

[v] ANSI/BHMA A156.13, Mortise Locks and Latches. Builders Hardware Manufacturers Association (BHMA), New York, NY, 2011.

[vi] Barrier Technology Handbook, SAND77-0777. Sandia Laboratories, 1978. pp. 16.3-39

[vii] Critical Intervention Services assisted window film manufacturer Solar Gard Saint-Gobain in 2015 in conducting a series of timed penetration tests of unprotected tempered glass windows and glazing reinforced with anti-shatter film. The author personally supervised and witnessed these tests.

[viii] Sedensky, Stephen J. Report of the State’s Attorney for the Judicial District of Danbury on the shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School and 36 Yogananda Street, Newtown, Connecticut on December 14, 2012. Danbury, Ct.: Office of the State’s Attorney. Judicial District of Danbury, 2013. Print.

[ix] UFC 4-022-02, SELECTION AND APPLICATION OF VEHICLE BARRIERS. US Department of Defense, N.p.: 2010.

[x] Guide to Active Vehicle Barrier (AVB) Specification and Selection Resources. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Washington, DC, 2016.