Egress Design and The Active Shooter Threat (Pt. 10)

Egress planning is often regarded as a life safety matter with influence on security, but otherwise a discipline independent from physical protection. However, when preparing facilities for active shooter violence, egress design should be approached as an integral component of our protective strategy.

As discussed in earlier articles in this series, security measures and facility preparations should be carefully designed to augment and anticipate the actions of building occupants. For people located at ground level during an attack or in building locations without safe refuge options, escape (what DHS calls ‘Run’) is the preferred response. To effectively facilitate this response, escape routes should be readily available that permit fast and unobstructed egress to safe outdoor locations away from the facility.

Although all buildings are required to comply with life safety codes related to emergency egress, International Building Code (IBC), NFPA 101, International Fire Code (IFC), and municipal codes often fall short in considering the unique dynamics of evacuation during armed events. Historically, these codes were designed with fire as the focus and don’t fully account for issues such as severe impairment of evacuees due to sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activation, the unpredictable actions of mobile attackers, and lack of situational awareness that may render multiple exit routes unsafe or at least perceived by evacuees as potentially-dangerous.

Many facilities rely on the advice of fire marshals and the results of inspection reports as a measure of readiness. Candidly speaking, this is a major concern. Aside from the inadequacy of current regulations, I often find violations of existing code during my work as a consultant that have somehow survived years of inspection.

So let’s take a walk beyond IBC and NFPA and explore considerations for designing an egress plan optimized to support response actions during active shooter events.

Egress Routes

To ensure building occupants have options for escape regardless of an attacker’s location, alternate egress routes should exist from all normally-occupied areas providing versatile access to safe exits. In most situations, providing two or more alternate egress paths from each occupied area (routed in different directions) is sufficient.

In newly-constructed buildings, identifying alternate egress paths isn’t usually difficult. In facilities constructed before modern building code, options are often limited.

During the 2008 assault on the Leopold Café in Mumbai, approximately 30 people were eating dinner in a narrow corridor of booths located on the second level when the attack commenced.[1] There was only a single stairwell and no room on the second floor capable of safe refuge. Fortunately for those on the second floor, the terrorists were satisfied after killing ten people and wounding numerous others and never noticed the unlocked door discreetly leading upstairs.

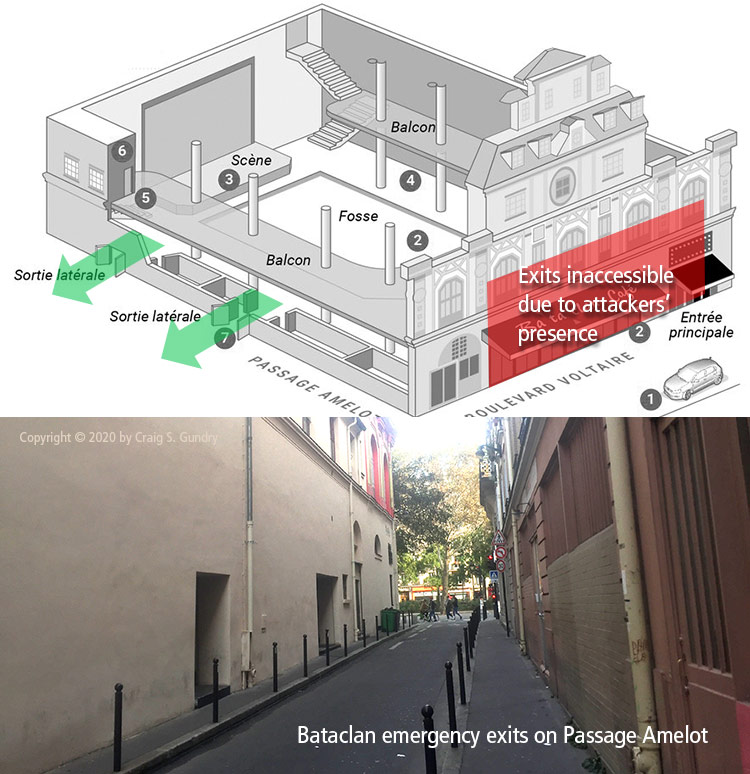

The Bataclan Theater in Paris, attacked by Islamic State terrorists in 2015, was another example of a building with limited escape options. At the time of the attack, there were three exits accessible to the public. One was the main entrance on Boulevard Voltaire and two emergency exits which discharged into an alley on the south-side of the building.[2] With the main entrance blocked by the terrorists’ presence, people located on the dance floor and north-side of the building had no way to escape without passing the attackers’ aim.

Installing new exits is the obvious solution to this problem. However, in situations where there are no options due to adjacent buildings (such as the Bataclan Theater) or similar circumstances, consider upgrading or constructing rooms for safe refuge purposes. As an additional measure, explore options for providing unconventional routes of escape as described later in this article.

The capacity of exits is another matter to consider. In situations where it is predictable that attackers will approach from a specific direction, expect a panicked reaction as everyone seeks to escape away from the gunman’s location. When faced with an imminent threat, people instinctively flee the direction of harm. Now if there are few people in the area, this type of reaction usually poses no special problems. But locations where this concern arises are often highly-populated and confined areas with limited exit options.

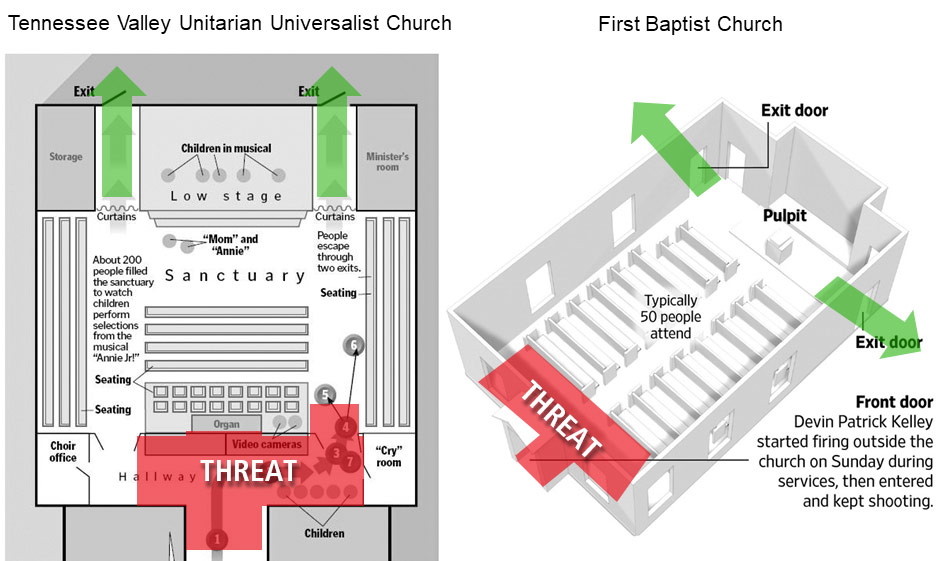

As discussed in Part 6 of this series, many armed attacks by outsider adversaries originate through public entrance doors and shooting commences immediately. This behavior has been very consistent in attacks against public buildings such as nightclubs, churches, and museums. In this situation, the natural reaction of people is to flee toward the opposite side of the room often resulting in tripping, trampling, and a bottleneck near whatever exit doors are present.

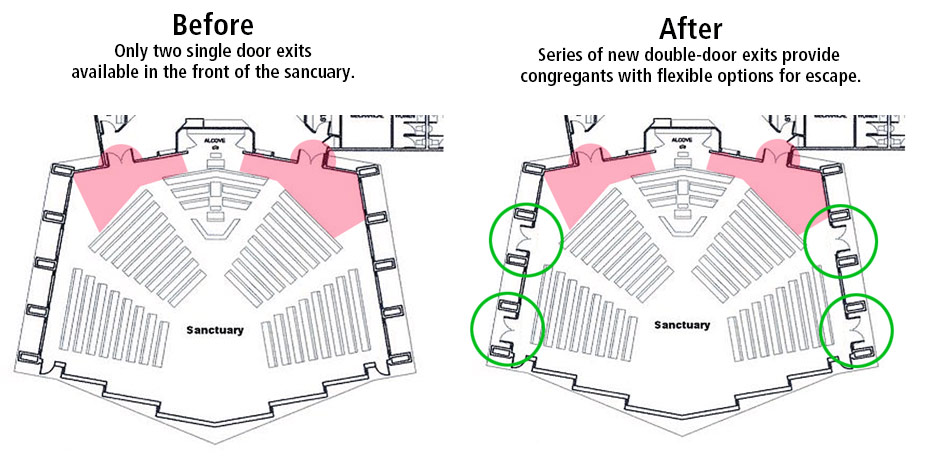

In some cases, the presence of furniture and other obstructions prohibit many from even reaching the exits. This situation has been especially common in attacks against church sanctuaries where the location of pews often block people from quickly reaching exits in the front of the room.

If this concern is foreseen during the initial design phase, solutions are often easy and don’t require major investment. For those with existing buildings, remedy often involves some expense.

If dangerous congestion is predicted at single-door exits, consider enlarging the present exits with the use of double-doors. If enlargement is insufficient or the situation prohibits modifying existing exits, consider installing new exits as illustrated in the following example.

In some cases, the situation can be eased by simply working with what’s available. In several buildings we’ve assessed with this concern, locked doors were present in areas where congestion was predicted providing access to service corridors or private hallways. By unlocking these doors and equipping them with appropriate hardware, we can provide an additional route of escape and ease congestion at the existing exits. However, implementing this solution may require other measures to address new concerns about public access into previously secured areas.

As a final point about escape paths, egress routes should be intuitive and simple to navigate under high-stress conditions. Several years ago I conducted an assessment of a community center building during the final phase of a major renovation. Unfortunately, most construction was nearly finished before we had a chance to offer useful comment. One of my greatest concerns in this situation was the addition of a new building level (earmarked for after-school programs) featuring two stairwells that discharged one level below into a second-floor hallway. After exiting to the second floor, evacuees were required to proceed down the hall to access a different stairwell in order to reach the first-floor exits. Despite the approval of local authorities, this type of complex egress path should be firmly avoided in active shooter planning. In the absence of any alternatives, our advice was to build a robust safe room in the kids’ area with sufficient capacity and train staff that lockdown is their only safe response during an attack.

Exit Signage

Exit signage should be clearly visible inside all work areas and hallways and direct evacuees to the most accessible stairwells or discharge doors. These are obvious points, but this subject is a common problem in many facilities. Where I encounter this issue most frequently is in renovated buildings that have changed their original room configuration or created expansive workspaces with cubicle walls. When facilities reconfigure walls and don’t update exit signage correspondingly, the result is often chaos—Signage directing evacuees to dead ends or locked doors, signage leading into areas with no further direction, locations where no signage is visible, etc.

Another problem, albeit less common, are situations where signage was incorrect from the beginning. Some time ago, I encountered a facility where the exit signage plan was similar to a puzzle game. Most arrows directed me in a circuitous loop around the outside of the floor and nowhere near the exit stairwells (which were positioned in interior hallways). Realizing I was walking in a circle, I followed alternate directional arrows and found myself at a dead end elevator landing with no nearby exits. Bear in mind, we’ve been conducting assessments of this type for years. If I can’t find my way out of a building, it’s likely a deathtrap during an active shooter attack.

If a building is configured with tall cubicle arrangements or corridors constructed of glass walls, consider placing directional signage on the floor if overhead visibility is a problem. In facilities like this, ceiling-mounted exit signage is often difficult to locate due to obstruction or the hall-of-mirrors type atmosphere often created in narrow corridors lined by glass. In these cases, providing additional signage on floors is often effective.

Emergency Stairwells

Exit stairwells should be well illuminated and clear of obstructions. Although these points are universally mandated under building and fire codes, this is another common area of concern.

On the subject of stairwell lighting, IBC permits illumination levels of 1 fc (10.8 Lux) and NFPA dictates 10 fc (108 Lux).[3] [4] Regardless of your location and regulatory mandates, I strongly recommend adopting the NFPA specification of 10 fc (108 Lux) as a minimum guideline. Over the years, I have assessed a number of facilities (particularly in Europe and the Middle East) where stairwell illumination was so poor I needed to use a flashlight to safely navigate the stairs.

Obstruction is another common problem. In the absence of adequate storage rooms, many facilities resort to stairwell landings as convenient spaces for overflow.

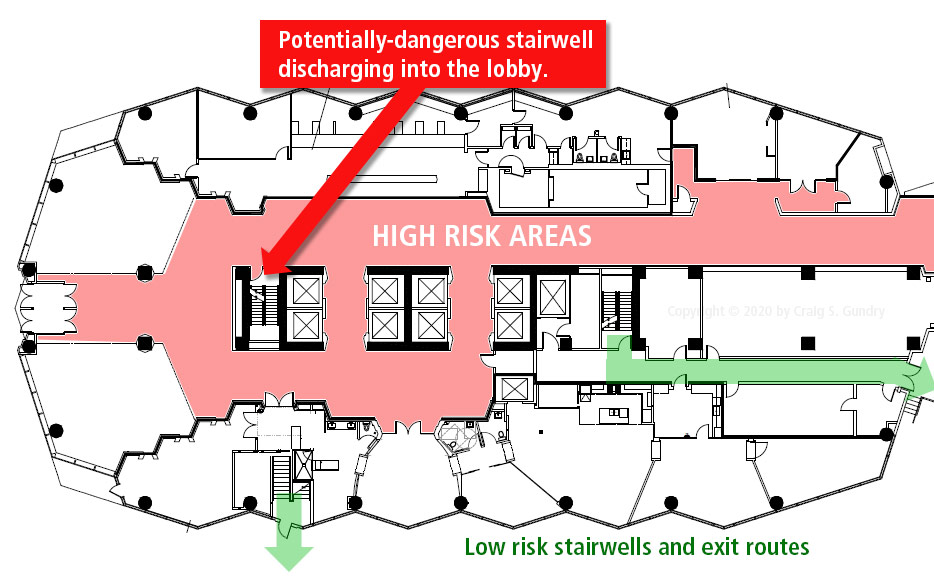

The location of stairwells is another issue to consider. In armed attacks against multi-floor buildings, the ground-level is often where the attack originates and may be a dangerous location while an event is active. If building occupants are not aware of the exact location of the threat, the combined effects of fear and lack of situational awareness may make people hesitant to evacuate if they need to navigate through interior hallways to access exits. This issue is often compounded further by the effects of the SNS on problem-solving ability.

To address these concerns, emergency stairwells should ideally discharge directly outdoors through exit doors at ground-level. Stairwells that discharge into lobbies or central hallways should be strictly avoided. If a facility has stairwells that discharge into potentially hazardous areas, employees should be warned of which stairwells to avoid as part of their active shooter training.

If an exit stairwell has multiple doors at ground-level, signage should be clearly visible indicating the proper door for discharge. Although this is not a common problem, I occasionally encounter situations where there are multiple doors at the base of a stairwell and no clear indication of which is the proper exit door. In this situation, choosing the wrong door may be a fateful decision.

Another matter to consider is the possibility of stairwells being used by attackers in navigating the building. During attacks inside multi-level structures, adversaries frequently use stairwells to move between levels. A few examples include attacks at the Virginia Beach Municipal Center (2019), Corinthia Hotel Tripoli (2015), and Washington Navy Yard (2013).[5]

Addressing this concern raises several challenges.

First, it is often cost-prohibitive to install CCTV cameras in stairwells in a manner suitable for tracking movement between floors (and especially in high rise structures). So if we have a control room employing CCTV to monitor the progress of attackers, stairwells are often a blind spot. Second, although IBC permits interior stairwell doors to be locked against entry from the stairwell side, code requires that interior stairwell doors are “capable of being unlocked simultaneously without unlatching upon a signal from the fire command center…[or] signal by emergency personnel from a single location inside the main entrance…” [6] NFPA regulations are different in detail, but the same concern is present. As discussed further in this article, the fail-safe operation of electrified locks is a major concern during active shooter attacks.

To address the possibility of adversaries navigating floors by stairwell, it may be permissible in some locations to install barriers inside existing stairwells featuring secured egress doors and exit bar devices to restrict upward movement. The photo below is an example of this type of barrier using wire mesh and an acrylic panel to prevent manipulation of the door handle. Although I like this approach in concept, code requirements should be carefully assessed before implementing this type of measure.

If the Design Basis Threat is an outsider adversary and placing barriers inside stairwells is permissible, I recommend installing them between ground-level and the next higher floor. This recommendation is based on the fact that most attacks by outsiders initiate at ground-level. In the case of buildings with interior public staircases providing access to second or third levels (such as a hotel with a mezzanine), the placement of stairwell barriers should be adjusted accordingly.

Exit Doors

Exit doors should be clearly visible and identified by overhead signage. Although this is not a common issue of concern, situations occasionally arise where architects have visually concealed the exit doors to create a unified aesthetic appearance. Following is an image illustrating this concern provided by Lori Greene, Manager of Codes & Resources at iDigHardware (Allegion).

Avoid the use of electromagnetic locks on egress doors!

Although mag locks offer versatile benefit in access control design, they present several problems during active shooter attacks. First, building and life safety codes universally require that egress doors equipped with mag locks fail safe (unlocked) during fire alarms. In this situation, every alarm pull station inside the building is a ‘virtual master key’ and will compromise all doors equipped with mag locks with one pull of a handle.[7] We have had multiple attacks where fire alarms were manually activated by building occupants (e.g., 2013 Washington Navy Yard), activated by smoke or dust (e.g., 2018 Marjory Stoneman Douglas HS, 2008 Taj Mahal Hotel Mumbai, etc.), or used by attackers to deceptively herd victims outdoors for ambush (e.g., 1998 Westside Middle School, 2013 UCF, 2015 Corinthia Hotel Tripoli, etc.).[8] [9] [10]

In addition to fire alarms, mag locks also fail safe if electricity is disrupted for any reason such as an extended power outage or if lines are damaged during an explosion. This is a particular concern in situations where the Design Basis Threat includes terrorists employing body-worn IEDs.

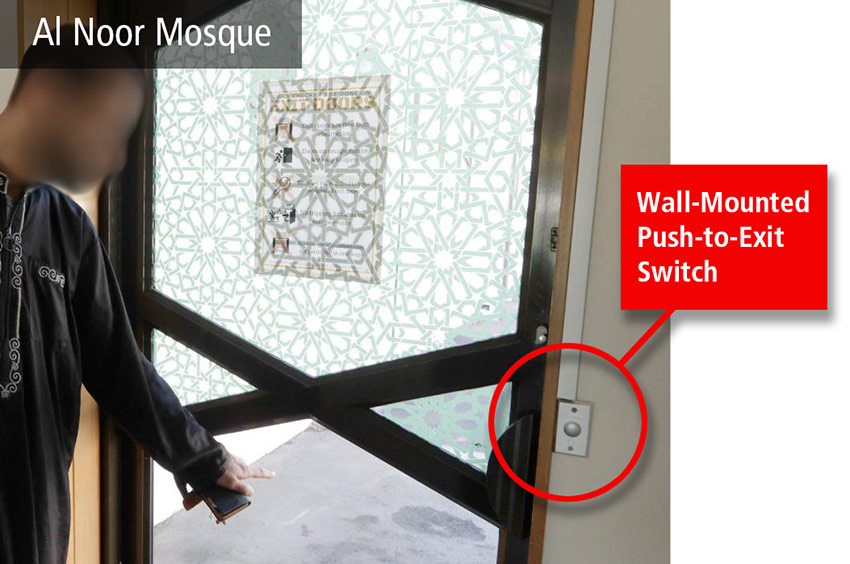

As an added concern, electromagnetic locks require door-mounted exit hardware (e.g., switch, lever, etc.) or alternatively, an exit sensor to unlock egress doors when an alarm is not activated. In many facilities I encounter, solitary wall-mounted push-to-exit (PTE) switches are used for this purpose despite code requirements stipulating door-mounted hardware or exit sensors. Furthermore, PTE switches used for this purpose are often small in size and easily overlooked when people are trying to escape under high stress conditions. Poor placement of PTE switches compounds this problem even further. During assessments, I often find PTE switches mounted away from doors in a manner that requires evacuees to stop and scan the area for a switch.

As a tragic example of this concern, in the 2019 shooting at the Al Noor mosque in Christchurch, 17 people were killed while trapped at an exit door operated by a PTE switch. [11] It is unclear from news reports whether the door failed to open because of an electrical problem or if there was difficulty by evacuees in locating and operating the PTE switch.

Exit sensors for mag locks often pose a different problem. If an exit sensor is placed above doors in a high traffic area, every time someone passes the sensor the door is unlocked. I’ve encountered many facilities where intrusion was as simple as waiting outside a door for a few minutes and listening for a click.

An even greater concern is when facilities opt not to install PTE switches or exit sensors on doors as a means of restricting use for fire evacuation only. The image below displays a bank of controlled exit doors at the entrance of an expo hall. To direct patrons to a nearby revolving door, the facility management decided (in violation of code) not to install PTE switches or exit sensors. When I inquired about this matter, I was assured that the fire alarm and/or control room operator would disengage the doors during an emergency. Nevertheless, if the operator is disabled or delayed in responding to an attack, the consequences of mass evacuation through this area would be tragic.

For access control purposes, we generally recommend using electrified panic bar devices or electric strikes with mechanical hardware. During an evacuation, electrified exit bar devices operate identically to mechanical exit bars—push the bar and the door opens. Aside from ease of operation, doors equipped with electrified exit bars and electric strikes can remain secured during power disruption and fire alarms (withstanding stairwell doors and other situations as defined by code).

As a final point about access control, avoid the use of delayed egress on exit doors. Many facilities employ egress delays (15-seconds or 30-seconds) as a means of discouraging occupants from exiting through doors reserved for emergency purposes. Although egress delays are often useful for channeling occupants to designated exits, any measure which delays escape during an attack increases the risk of avoidable casualties.

The following video illustrates how long 30 seconds is while standing at an exit door during an active shooter attack.

Unconventional Exit Options

When normally discussing the topic of egress, ground-level exit doors are presumed to be the main points of building discharge. However, during active shooter events, there are often many opportunities for escape that don’t meet the standards of fire code.

For people located on higher building levels, it is often safer to escape upward toward the roof than downward through stairwells. During the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack, employees of a company located on the third floor above the Charlie Hebdo office sought safety on the rooftop due to concern about gunfire penetrating their office. In the 2004 attack at the Oasis Compound in Saudi Arabia, two people hid on a roof for two days before rescue. Several employees at Washington Navy Yard’s Building 197 also took refuge on a roof rather than risk harm below.[12]

As part of active shooter training, advise employees about the availability of the roof as a safe area. And if the roof is presently locked, consider placing an escape key near all rooftop doors specifically for use during an active shooter event. If safety concerns override the decision to place escape keys near doors, consider installing electrified locks on the rooftop doors that can be released through a lockdown event macro programmed in the building’s access control software.

During an attack, any window less than three stories or aperture large enough to crawl is a potential route of escape. In the 2007 shooting at Virginia Tech’s Norris Hall, students in Room 204 escaped by jumping out the second story windows of their classroom.[13] During the 2016 siege at the Pulse nightclub, eight people escaped through an air conditioning vent with police assistance. In the 2013 attack at the Westgate Shopping Mall, people in a restaurant also escaped by crawling through an air vent.

If our present building has windows and other unconventional escape opportunities, make note of these options and advise employees during active shooter training. Simply mentioning the examples already cited in this article calls attention to the possibilities and provides a point of reference if employees ever find themselves trapped during an attack.

Now if we are working with an existing structure, it usually doesn’t make sense from a cost-benefit perspective to install new windows or make other building alterations specifically to facilitate unconventional modes of escape. An exception to this might be situations like the Bataclan Theater (described earlier in this article) where the absence of exits is a major concern and there are no options for remedy.

When designing new facilities, consider placing windows in select locations where it is likely people will be trapped during an attack. One example is public restrooms. Although public restrooms rarely feature door locks, they are commonly used by people seeking refuge during active shooter attacks. If we anticipate this problem and the restroom is adjacent to an exterior wall at ground level, install a 24” tall horizontal sliding window just below the ceiling to provide anyone trapped in the restroom with a possible means of escape. If this had been done at the Pulse nightclub, thirteen people might be alive today.[14]

[1] Details provided by a confidential source during the author’s visit to the Leopold Café in 2016.

[2] Details confirmed during the author’s visit to the Bataclan Theater in 2018.

[3] 2015 International Building Code. Chapter 10 (Means of Egress). International Code Council. N.p. 2015.

[4] NFPA 101 7.8.1.3 (1)

[5] After Action Report. Washington Navy Yard. September 16, 2013. Internal Review of the Metropolitan Police Department. Metropolitan Police Department. Washington, D.C. July 2014.

[6] 2015 International Building Code. Chapter 10 (Means of Egress). International Code Council. N.p. 2015.

[7] As a caveat to that statement, NFPA 101 states that the pull stations don’t have to unlock the doors: The activation of manual fire alarm boxes that activate the building fire-protective signaling system specified in 7.2.1.6.2(4) shall not be required to unlock the door leaves. (Comment by Lori Greene, iDigHardware)

[8] Initial Report Submitted to the Governor, Speaker of the House of Representatives and Senate President. Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission. January 2, 2019.

[9] After Action Report. Washington Navy Yard. September 16, 2013. Internal Review of the Metropolitan Police Department. Metropolitan Police Department. Washington, D.C. July 2014.

[10] Harms, A.G. UCF After-Action Review. Tower #1 Shooting Incident. March 18, 2013. Final Report. N.p. May 31, 2013.

[11] “’It doesn’t open’: Christchurch mosque survivors describe terror at the door” Stuff. March 28, 2019, https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/christchurch-shooting/111632051/it-doesnt-open-christchurch-mosque-survivors-describe-terror-at-the-door. Accessed 25 March 2020.

[12] After Action Report. Washington Navy Yard. September 16, 2013. Internal Review of the Metropolitan Police Department. Metropolitan Police Department. Washington, D.C. July 2014.

[13] Mass Shootings at Virginia Tech. April 16, 2007. Report of the Review Panel. Virginia Tech Review Panel. August 2007.

[14] Harris, Alex. “New details emerge about where the victims of the Pulse massacre died.” Miami Herald. June 14, 2017, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/state/florida/article144586874.html. Accessed 13 March 2020.

Craig Gundry

Copyright © 2020 by Craig S. Gundry, PSP, cATO

CIS consultants offer a range of services to assist organizations in managing risks of active shooter violence.

Contact us for more information.

Recent Comments