Enhancing Workplace Safety: The Importance of Utilizing Outside Experienced Experts and The WAVR-21 Assessment

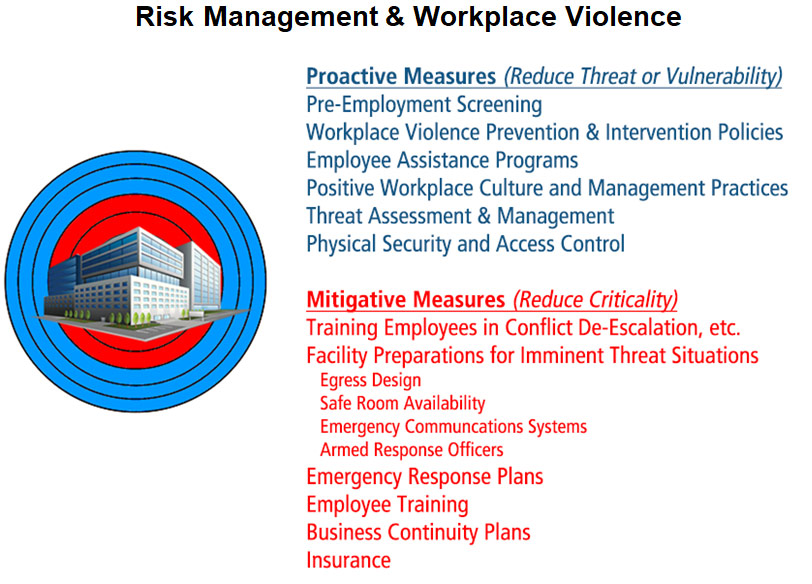

Workplace violence is a serious and increasingly prevalent issue, requiring meticulous and impartial assessment for effective mitigation and prevention. It is vital that organizations leverage the expertise of external specialists in workplace violence assessment to navigate this complex and sensitive landscape. These professionals bring a unique blend of neutrality, proficiency, and experience that ensures a comprehensive and accurate evaluation of workplace violence risks.

External experts, unburdened by ties to the company or its employees, offer an unbiased evaluation of workplace violence risks, navigating the situation without being influenced by internal politics or personal relationships. Their impartiality is vital for an unfiltered assessment, identifying potentially hidden or understated risks, thus ensuring an accurate and comprehensive understanding of the situation.

Their specialized knowledge and experience further bolster the effectiveness of their assessments. Equipped with the latest research, industry best practices, and legal requirements associated with workplace violence, these experts can identify early warning signs and devise strategies to counter potential threats. Their in-depth understanding and practical expertise make them invaluable assets in providing sound advice that can significantly mitigate workplace violence risks.

One of the key tools these experts leverage is the Workplace Assessment of Violence Risk (WAVR-21), an empirically based structured professional judgement instrument (SPJ) designed to evaluate the risk of violence within a workplace environment. Developed by leading experts in threat assessment, the WAVR-21 is a comprehensive approach to workplace violence, incorporating 21 dynamic and static factors relevant to this issue.

The WAVR-21’s methodical approach ensures a balanced and accurate evaluation by encouraging the consideration of multiple information sources. It aids in identifying the context and nature of the threat, as well as the personality and situational factors influencing an individual’s behaviors. Crucially, the tool guides the development of effective management and intervention strategies.

The importance of having an outside expert who is properly trained in use of the WAVR-21 instrument cannot be overstated. These professionals have undergone specific training to conduct assessments accurately and effectively. They possess a deep understanding of different risk factors, ensuring an accurate and nuanced assessment. Additionally, they can incorporate the tool into a broader assessment strategy, considering other relevant factors such as organizational culture, policy, and procedures.

WAVR-21 qualified professionals are trained to interpret the results of the assessment in a meaningful way, considering the specific context and dynamics of the workplace. They can provide detailed recommendations for risk reduction measures, intervention strategies, and ongoing management practices, thus ensuring a thorough, informed assessment tailored to the unique circumstances of each workplace.

Another crucial benefit of engaging an outside expert is their ability to maintain confidentiality and trust, often creating a secure environment for employees to express their experiences and concerns. Given the complexities of legal and compliance issues associated with workplace violence, outside experts adept at navigating these regulations and standards can ensure a comprehensive, legally sound assessment, helping organizations avoid potential liabilities.

Upon completion of the assessment, the outside expert can provide expert guidance in developing preventive measures and response protocols. Their recommendations, grounded in industry best practices and tailored to the organization’s specific needs and challenges, strategically equip the organization to prepare for and mitigate potential threats effectively.

In conclusion, engaging a WAVR-21 certified outside expert for workplace violence assessment isn’t just a prudent decision—it’s a vital strategic move that ensures the long-term safety and success of an organization. By combining their expertise with the structured approach of the WAVR-21, these experts ensure a comprehensive evaluation of potential risks and a robust strategy to mitigate workplace violence. The result is a safer, more secure work environment that promotes productivity and employee well-being.

Finding an expert

Finding an expert, specifically a WAVR-21 qualified professional for workplace violence assessment, involves a few steps:

- Professional Associations and Organizations: Professional associations related to workplace violence prevention and threat assessment are excellent resources. They also provide resources and information that can be helpful in your search.

- Referrals: Talk to peers in your industry or a trusted legal advisor who may have used such services before. They can provide a firsthand account of their experiences and recommend experts they’ve found reliable and competent.

- Online Search: A simple online search can also help you identify potential experts. Look for professionals who specialize in workplace violence assessment and are WAVR-21 certified. Ensure to verify their credentials and look for reviews or testimonials.

- Training Providers: Institutions that provide WAVR-21 training may also offer consultation services or be able to recommend certified professionals. The creators of WAVR-21, for instance, offer training and consultation services.

- Consulting Firms: There are many consulting firms specializing in workplace violence prevention and threat assessment that employ WAVR-21 certified professionals. Look for firms that have a solid reputation and extensive experience.

Once you have identified potential experts, consider the following:

Experience: Check the expert’s experience in workplace violence assessment. How many assessments have they conducted? What types of organizations have they worked with? Do they have experience in your specific industry?

Qualifications: Ensure that they are appropriately trained in use of the WAVR-21 instrument and check for any other relevant qualifications or certifications.

Approach: Talk to them about their approach to violence risk assessment. Does it seem comprehensive and systematic? Does it align with your organization’s needs and culture?

References: Ask for references from previous clients. Reach out to these references to learn about their experiences with the expert.

Remember that the process of finding an expert might take some time, but it is an investment that could potentially save lives, prevent harm, and protect your organization in the long run.

Recent Comments