Securing Residential Communities: Comprehensive Strategies for Stakeholders

In every jurisdiction, communities across the United States are susceptible to individuals with malicious intent. It is crucial for stakeholders to remain vigilant in identifying criminal activities and the individuals involved. However, the impact of these criminal activities often affects the community more than the individuals perpetrating the crimes. Therefore, addressing criminal activity promptly upon discovery should be the top priority for housing operators as it provides the best defense against recurring incidents. Long-term criminal issues typically arise from a failure to identify crime and implement effective mitigation strategies when crimes occur within or near the community or property.

Challenges and Strategies

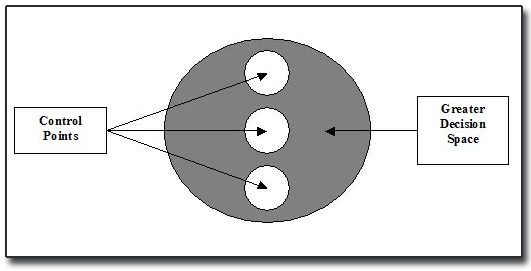

The management of drug use incidents, gun-related incidents, and other forms of violence has become increasingly challenging in multifamily community environments across the country. Housing owners and managers often struggle with allocating resources and finding the right expertise to handle these issues internally. Dealing with crime and violent incidents in residential communities requires deliberate and proactive action. Passivity will only embolden those involved in such incidents. Strategies must be carefully crafted and executed to gain even the slightest advantage in the fight against criminal activity. It is essential to take a holistic approach, ensuring that policies are enforced, the environment is designed and maintained to prevent crime, residents actively collaborate and communicate with the housing organization and local law enforcement.

Comprehensive Security Measures and Residential Communities

To meet the strategic needs of criminal event mitigation, housing organizations can consider various initiatives suggested by experts in communities of all sizes throughout the United States. Here are fifteen ideas to inspire preventive measures against criminal activities:

- Enforce current guest rules and resident lease terms.

- Review, strengthen, and enforce tenant leases pertaining to social responsibilities.

- Develop a written security program that serves as a roadmap for addressing the organization’s security activities and processes.

- Engage in open dialogue with local law enforcement and tap into the resources they can provide.

- Discourage unstructured medium/large social gatherings.

- Prohibit loitering and trespassing on the property.

- Educate residents and visitors about conduct expectations through written materials.

- Employ professional security enforcement personnel.

- Establish a communication channel for residents to report unsavory behaviors to management and law enforcement.

- Utilize social media and technology as tools to enhance security.

- Implement community crime prevention practices that have been vetted.

- Utilize in-house security expertise and advisors.

- Review HUD guidelines for safe housing.

- Explore available grant opportunities for assistance.

- Seek advice from legal counsel and prosecutorial experts to identify additional lawful options, if necessary.

Investing in Social Capital Strategies for Crime Reduction

In addition to comprehensive security measures, social capital investment strategies also play a vital role in crime control. Social capital investments are rooted in a network of relationships and norms that facilitate cooperation for mutual benefit. They contribute to crime reduction by impeding criminals’ activities, fostering a sense of community ownership, and supporting individuals at risk. Efforts to reduce crime must include a focus on establishing relationships between stakeholders and coordinating actions to address environmental and social factors that contribute to criminal behavior.

Here are some additional examples of how social capital can be utilized to reduce crime:

- Neighborhood social events: Hosting food gathering events like BBQs and resident competitions for the best-kept and decorated home can foster a sense of community and strengthen relationships among residents. These events provide opportunities for neighbors to connect, build trust, and look out for one another, which can deter criminal activity.

- Volunteer programs: Encouraging residents to participate in volunteer initiatives, such as community clean-up projects or mentoring programs, can promote social cohesion and create a stronger sense of ownership and pride in the community. When residents actively invest their time and effort in improving the neighborhood, it creates a less favorable environment for criminal behavior.

- Community education workshops: Organizing workshops on topics such as crime prevention, personal safety, conflict resolution, and mediation can empower residents with knowledge and skills to protect themselves and effectively address issues within the community. By promoting education and awareness, residents become more proactive in maintaining a secure environment.

- Youth mentorship programs: Establishing mentorship programs that pair responsible adult volunteers with at-risk youth provides positive role models and guidance for young individuals who may be vulnerable to engaging in criminal activities. By offering support and guidance, these programs help steer youth towards productive and law-abiding paths.

- Community resource centers: Creating community resource centers where residents can access information, support services, and resources related to crime prevention, mental health, substance abuse, and social services can contribute to reducing crime. These centers serve as hubs for residents to seek help and guidance, fostering a safer and more supportive community.

Managing Criminal Activity in Apartment Communities

Managing criminal activity in apartment communities, particularly experiencing drug and gun violence, is a crucial aspect of maintaining a safe and secure living environment for residents. Property managers and landlords play a vital role in implementing effective strategies to prevent and address criminal activity. Here are some ways to manage criminal activity in apartment properties:

- Develop a Comprehensive Security Plan: Start by creating a comprehensive security plan tailored to the specific needs of the property. Assess potential vulnerabilities and identify areas where criminal activity is more likely to occur. Consider factors such as lighting, surveillance systems, access control, and alarm systems to enhance security measures.

- Install Surveillance Systems: Implementing a robust surveillance system with strategically placed cameras can act as a deterrent for criminal activities. High-quality cameras, both indoors and outdoors, can provide valuable evidence in case of incidents and help identify individuals involved in criminal behavior.

- Enhance Access Control: Limiting access to the property is crucial in managing criminal activity. Use key card or keyless entry systems to control who can enter the building and monitor visitor access. Secure all entrances and ensure that locks, gates, and fences are properly maintained to prevent unauthorized entry.

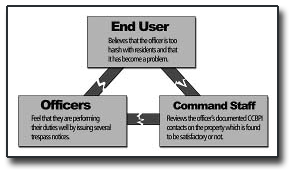

- Engage with Law Enforcement: Establish a positive working relationship with local law enforcement agencies. Regularly communicate with them about any concerns or incidents occurring within the property. Request their presence for community events and encourage them to conduct routine patrols around the area.

- Implement Background Checks and Tenant Screening: Conduct thorough background checks and tenant screenings to identify potential tenants with a history of criminal activity. This step can help prevent individuals with a propensity for criminal behavior from moving into the property.

- Encourage Community Involvement: Foster a sense of community within the property by organizing events and activities that encourage residents to interact with each other. A strong community can be an effective deterrent to criminal activity as neighbors are more likely to look out for each other and report suspicious behavior.

- Promptly Address Complaints and Concerns: Encourage residents to report any concerns or suspicious activities promptly. Implement a clear and confidential reporting system and ensure that residents are aware of how to use it. Take every complaint seriously and investigate reported incidents promptly.

- Implement a Zero-Tolerance Policy: Clearly communicate a zero-tolerance policy for criminal activity within the property to all residents. Enforce this policy consistently and take appropriate legal action against violators. By doing so, you send a strong message that criminal behavior will not be tolerated.

- Provide Security Awareness Training: Organize security awareness programs to educate residents about personal safety, recognizing signs of criminal activity, and the importance of reporting incidents promptly. Encourage residents to take necessary precautions, such as securing their units and reporting any suspicious behavior.

- Collaborate with Community Organizations: Engage with local community organizations and resources that specialize in crime prevention and community safety. These organizations can provide valuable insights, resources, and support to help manage criminal activity effectively.

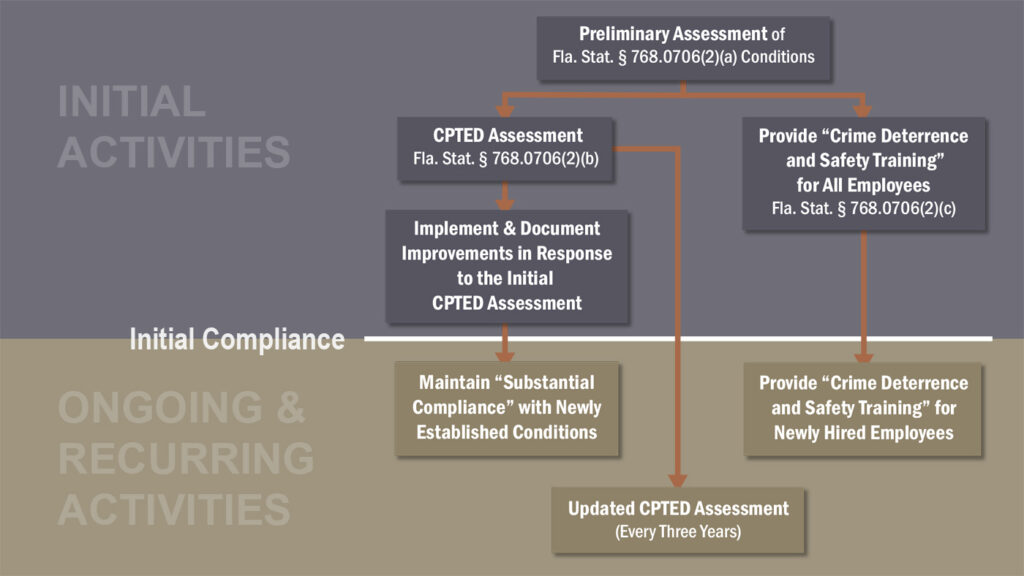

Ongoing Training and Education

Another key component of comprehensive security strategies is providing ongoing training and education for property managers, staff, and residents. Continuous training ensures that all stakeholders are well-equipped with the knowledge and skills needed to implement security protocols, handle emergency situations, and contribute to crime prevention. Property managers and staff should receive regular training on security best practices, incident response procedures, and the effective use of security technology. Residents should be educated on personal safety measures, recognizing signs of criminal activity, and the importance of promptly reporting incidents to the appropriate authorities. By investing in ongoing training and education, stakeholders can create a proactive and knowledgeable community that actively contributes to maintaining a secure living environment.

Conclusion

Managing criminal activity in housing communities requires a comprehensive approach that includes robust security measures, collaboration with community stakeholders, and ongoing training and education. By implementing a combination of preventive measures, leveraging collective efforts and resources, and fostering community engagement, stakeholders can create a safer and more secure living environment for residents. The examples provided in this article, demonstrate the power of social capital in reducing crime and strengthening community bonds.

It is important to recognize that crime prevention is an ongoing effort that requires continuous evaluation, adaptation, and improvement. Stakeholders must remain proactive in staying informed about emerging security threats, technology advancements, and best practices in crime prevention. By staying abreast of new developments, stakeholders can implement innovative strategies and respond effectively to evolving challenges.

Furthermore, fostering open communication and collaboration between stakeholders, including residents, property managers, security professionals, law enforcement agencies, and community organizations, creates a network of support and resources that can be harnessed to address security concerns effectively. By working together, sharing information, and coordinating efforts, stakeholders can develop a united front against criminal activities and foster a sense of collective responsibility for maintaining a safe and secure living environment.

In conclusion, enhancing security strategies for stakeholders in residential communities requires a multifaceted approach that combines comprehensive security measures, community collaboration, and ongoing training and education. By embracing these strategies and investing in social capital, stakeholders can create thriving communities where residents feel safe, connected, and empowered. Ultimately, the collective efforts and commitment of stakeholders pave the way for a more secure and harmonious living environment for all concerned as they set the standard of acceptable behavior for their community.